Communication

as the Ultimate Goal of English

Learning

for Spanish, Chinese, Japanese and

Thai

Students

KANCHANA PRAPPHAL

Affective variables play an important role in language acquisition, although measurement of affect faces empirical difficulties. Dunkel (1948) hypothesized two aspects of affect in second language study, motivation and intensity. “Motivation” is used to refer to objectives and purposes while “intensity” is used to show degree of effort. Gardner and Lambert (1972) extended the theory of affect in language acquisition by differentiating two types of orientation, integrative and instrumental. The former involves learning the target language in order to communicate and interact with, or to become a member of the target language community. The latter focuses on learning the language for utilitarian purposes. The instrumental learner does not have the intention of interacting socially with, or becoming like, members of the target language community.

However, the theoretical

distinction between instrumentality and integrativeness is unclear.

Lukmani (1972) reported that degree of instrumental orientation was a better

predictor of language achievement for Indian women in Bombay than degree

of integrative orientation. Genesee (1978) also found different results

from those predicted by Gardner. Sixth and eleventh grade anglophones

in Quebec who were more successful in learning French were instrumentally

motivated rather than integratively motivated. This tends to refute

Gardner’s prediction that an integrative orientation results in superior

language achievement. Oller, Hudson, and Liu (1977) found a significant

negative correlation between English proficiency of Chinese university

students in the U.S. and an integrative measure indicating willingness

to stay permanently. Oller, Baca, and Vigil (1977) found that a group

of Mexican-American women who rated Anglo-Americans more positively than

Mexicans on personal traits tended to score low on an English

proficiency test. Johnson and Krug

(1980) found no significant

correlations between a modified

Gardner and Lambert questionnaire (1972) and several language tests (listening

cloze, dictation, oral cloze, MC Reading Match, etc.).

Possible explanations for the inconsistency of results are suggested by Oller and Perkins (1978). Contaminating sources of non-random variance include the approval motive, self-flattery, and response set. The approval motive may lead to answers based on what respondents believe to be socially acceptable. The self-flattery tendency results in positive self-ratings on attitudinal scales. Response set is the tendency for respondents to be consistent in expressing themselves on questions with similar content. In addition, the inconsistency of responses may be due to the instruments of affect. This study, thus, examines (1) whether the distinction between instrumentality and integrativeness exists when the affective questionnaire, using the repeated-measurement technique to check content and concurrent validity, is employed, and (2) whether subjects from different geographical, linguistic and cultural backgrounds have similar purposes in learning English.

METHOD

Subjects1

The investigation was

carried out in four different settings, the United States, Taiwan, Japan

and Thailand. 448 students participated in this study: 39 Spanish

speaking students (11 under-graduates and 28 graduates) at the University

of New Mexico who came from Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Columbia, Costa

Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Venezuela;

141 first-year Chinese

students from the National

Kaohsiung Teachers’ College in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan; 142 first-year Japanese

students from Baika Tanki College in Osaka, Japan; and 126 first-year Thai

students from the Faculty of Arts, Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok,

Thailand. The Chinese and Japanese students had studied English for

about 6 years while the Thai students had studied it for 10 years.

Instrument

The Affective Questionnaire used in the study was adapted from Oller, Prapphal, and Byler (1982)2. There were two major parts and each of those parts was subdivided into three subparts. In each subpart there were exactly three propositions to be agreed with or disagreed with on 7-point Likert-type scales ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Each proposition was stated in three different forms: two “direct” statements and one “indirect” statement. Thus there were three items per construct. There were 18 propositions to be rated: 36 “direct” and 18 “indirect”, 54 items in all. This format was used in order to cross-check responses.

To avoid having statements aimed at the same construct appear together, the order of presentation was randomized. The underlying design of the 18 constructs was as follows:

Part I:

Instrumentality (9 constructs of 2

items each = 18 items)

Set A:

Academic Purposes (3 constructs, 6 items)

Set B: Socio-Cultural

Purposes (3 constructs, 6 items)

Set C: Jobs and Personal

Benefits (3 constructs, 6 items)

Part II: Integrativeness

(9 constructs of 2 items each = 18 items)

Set A: Personal Preferences

(3 constructs, 6 items)

Set B: Ethnic Identity

(3 constructs, 6 items)

Set C: Self-Concept

(3 constructs, 6 items)

A systematic alternation of item valences are introduced into the design. This was done to discourage the students from marking the same position on all scales. In addition, this would allow for a possible check on whether the students gave similar responses to similar meanings. In the 36 direct statements aimed at 18 constructs as outlined above, a positively worded item was followed by a positively worded one, then two negatives, then a negative followed by a positive, and so forth throughout the 36 items — then all 36 items were presented in random order.

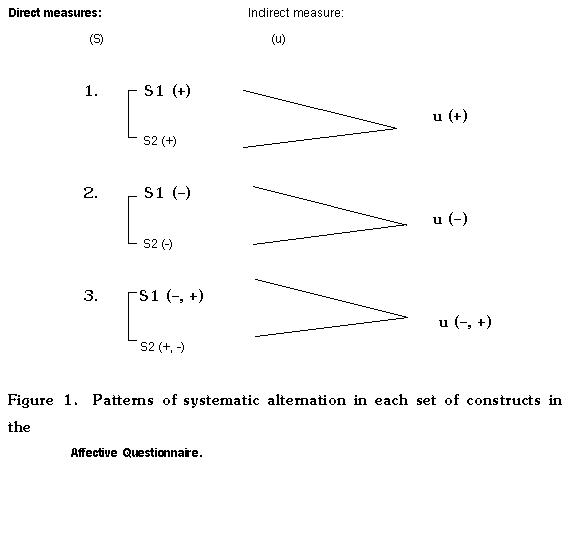

For the indirect statements, each item corresponded in its prepositional valence (affirmative or negative) to the first member of each direct item pair. Figure 1 shows the pattern of systematic alternation of item valences.

This alternation pattern was carried out to check on the reliability and validity of each item in the Affective Questionnaire. This was done based on the following three hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Convergence of means within each triplet. Item means within each triplet (2 direct and 1 indirect statements) should be approximately the same when the negative items are scored on reversed scales.

Hypothesis 2: Predicted signs of correlations. Items with the same valence should correlate positively while items with opposite valences should correlate negatively.

Hypothesis 3: Significance and magnitude of correlations. Items that have concurrent validity should be significantly and substantially correlated.

By examining these three hypotheses concerning items aimed at the same propositional meaning, the internal consistency of each triplet can be judged. The Affective Questionnaire was given in Spanish, Chinese, Japanese, and Thai to reduce the importance of the English language proficiency factor raised by Oller and Perkins (1978). To reduce meaningless consistency, a table of random numbers was used to arrange the items in scrambled order, except that all of the direct statements appeared ahead of the indirect ones.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To obtain an assessment

of reliability and tendency towards validity of the Affective Questionnaire,

the three hypotheses stated above were tested. The results indicated

that a repeated measurement technique used to check internal consistency

of responses as well as to investigate the concurrent validity of the affective

questions was found to be a reliable measure for the Spanish, Chinese,

Japanese, and Thai students. (The details of the analyses are given

in Ogawa, Byler and Oller (1981); and Prapphal, Oller, Yu, Ross, and Byler

(1982). A final investigation of the overall consistency of the Affective

Questionnaire was obtained by looking at the Cronbach alpha reliability

for each part and the whole questionnaire. The attitude scales included

only the items which indicated content validity (by examining each triplet

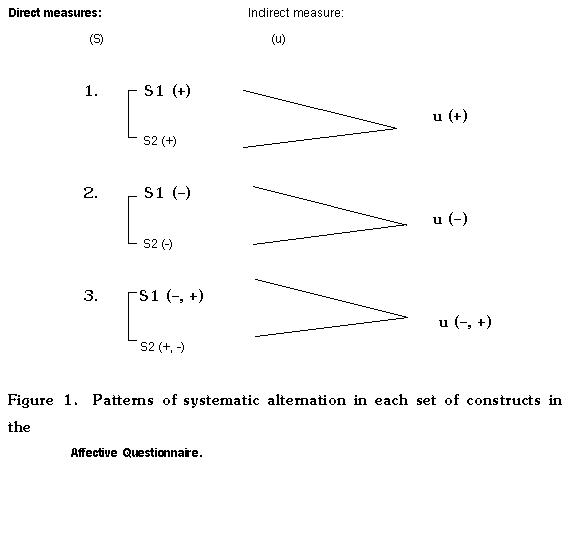

aimed at the same propositional content). Table 1 presents the reliability

coefficients of the Affective Questionnaire.

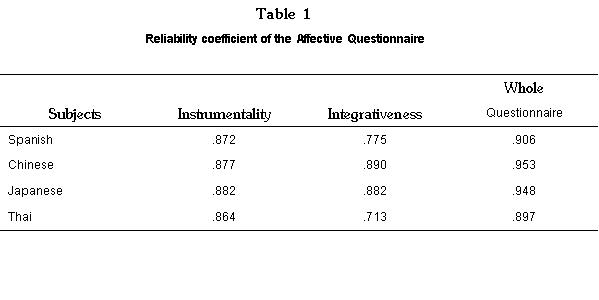

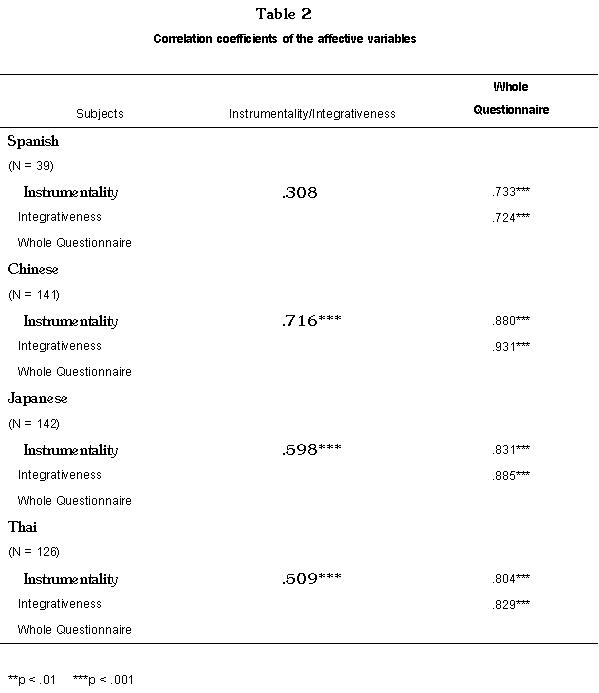

The reliability coefficients range from .713 to .9533 which indicates an acceptable level of consistency. The coefficients for Instrumentality, Integrativeness, and the whole questionnaire for the Spanish speaking subjects were .872, .775, and .906; .877, .890, and .953 for Chinese; .882, .882 and .948 for Japanese; and .864, .713, and .897 for the Thai subjects. To answer the first research question, “whether the distinction between instrumentality and integrativeness exists when the repeated-measurement technique questionnaire is used”, the SPSSX Pearson correlation subprogram was employed. Table 2 illustrates the correlation coefficients of the affective variables.

The results in Table

2 reveal that “Instrumentality” and “Integrativeness” were significantly

and positively correlated with each other in the Chinese, Japanese, and

Thai studies. The correlation coefficients were .716, .598, and .509

respectively. However in the Spanish study, the relationship was

found to be insignificant. This raises an interesting point.

The Spanish speaking students who stayed in the United States distinguished

“Instrumentality” from “Integrativeness” while the Chinese, Japanese, and

Thai students who study English as a foreign language did not differentiate

“Instrumentality” from “Integrativeness”. This suggests that students

don’t have to stay

in an English speaking country to feel “integrative”. These students might have been provided with a favorable enough language environment that they have developed positive attitudes towards the target language. On the other hand, the Spanish speaking students, despite living in an English speaking country, might want to identify with their own compatriots and might not try to mix with Americans. Therefore, they tend to differentiate “Instrumentality” from “Integrativeness”. In this case, Krashen’s Input Hypothesis (1980, 1985) might help explain the differences in the responses. One should study affect by examining the type of input that the learner is provided with rather than by separating affect into two distinct categories.

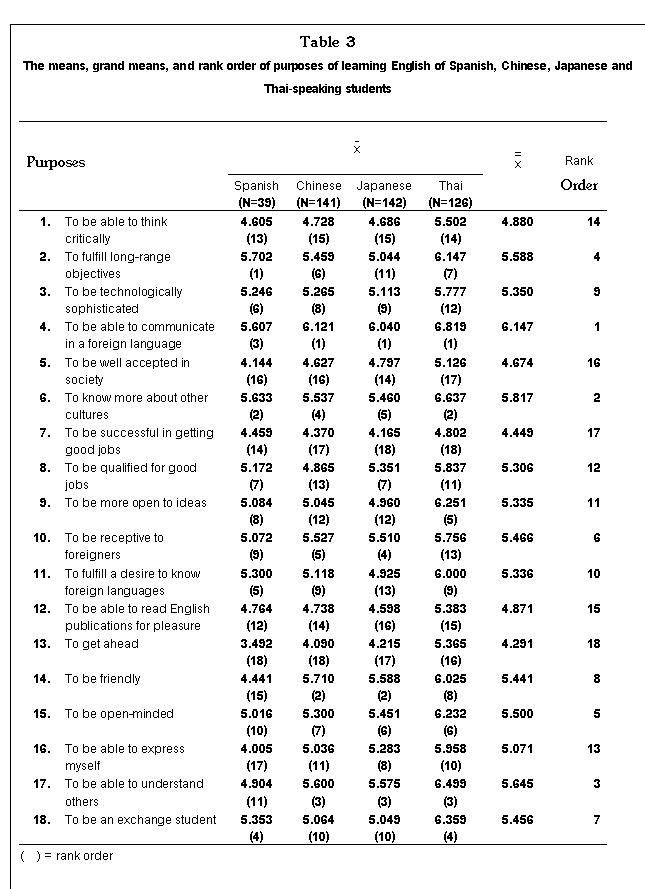

In addition, the fact that the Chinese, Japanese, and Thai students did not separate the two categories provides further evidence to support the problem of construct validity of affective variables. As Oller (1973:8) noted: “The very term affective variables which implies that there are many and that they are countable discrete variables may be somewhat misleading.” Therefore, emotions should not be treated as countable discrete variables. Rather than trying to identify affective variables, teachers should try to motivate students to learn and encourage a favorable language learning environment, no matter where it takes place, in either an ESL or EFL context. And that’s why the second research question, “why do students from different geographical, linguistic and cultural backgrounds learn English?” was further investigated. Table 3 gives the means, grand means and rank order of various reasons for studying English given by the Spanish speaking students as well as the Chinese, Japanese, and Thai students.

Of the 18 purposes mentioned in the Affective Questionnaire, “To be able to communicate in English” received top priority. This is indicated by the grand mean of 6.147 on a 7 point Likert scale. Although the Spanish speaking students rated this purpose third in rank, it was very close to the first, the difference being only .095. The reason that the Spanish speaking students rated “To fulfill long-range objectives” first may be due to the fact that many of them were graduate students while the Chinese, Japanese, and Thai students were undergraduates.

Other purposes which ranked higher than 5 by the four groups are “to know more about other cultures, to be able to understand others, to fulfill long-range objectives, to be open-minded, to be receptive to foreigners, to be an exchange student, to be friendly, to be technologically sophisticated, to fulfill a desire to know foreign languages, to be more open to ideas, to be qualified for good jobs, and to be able to express myself.” The objectives which were rated less than 5 by all groups are, “to be able to think critically, to be able to read English publications for pleasure, to be well accepted in society, to be successful in getting good jobs, and to get ahead”.

Other purposes which ranked higher than 5 by the four groups are “to know more about other cultures, to be able to understand others, to fulfill long-range objectives, to be open-minded, to be receptive to foreigners, to be an exchange student, to be friendly, to be technologically sophisticated, to fulfill a desire to know foreign languages, to be more open to ideas, to be qualified for good jobs, and to be able to express myself.” The objectives which were rated less than 5 by all groups are, “to be able to think critically, to be able to read English publications for pleasure, to well accepted in society, to be successful in getting good jobs, and to get ahead.”

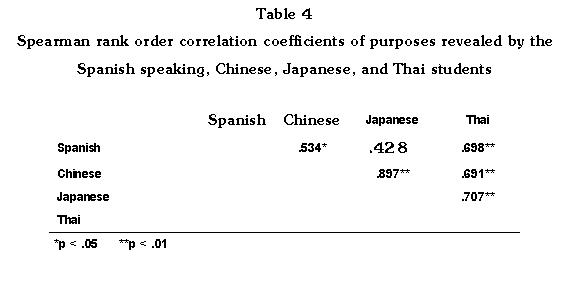

The above results were obtained from the grand means of all purposes. To find out whether the rank orders of the ratings of the four groups are significantly different or not, Spearman rank order correlation coefficients were computed. Table 4 presents the results.

CONCLUSION

The distinction between

“Instrumentality” and “Integrativeness” is not supported by the results

of this study. On the contrary, when checking the consistency of

responses in the Affective Questionnaire, by employing the repeated-measurement

technique, the respondents from different geographical, linguistic, and

cultural environments chose communication as their top priority.

The empirical evidence provided in this study, therefore, confirms the

fundamental aim of language learning: one learns a language to communicate

with others.

REFERENCES

Dunkel, H.B. 1948. Second-language learning. Boston: Ginn.

Gardner, R.C., and W.E. Lambert. 1972. Attitudes and Motivation in Second Language Learning. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House.

Genesee, F. 1978. Individual differences in second-language learning. Canadian Modern Language Review 34: 490 – 504.

Jakobovits, L.A. 1968. Research findings in language learning and teaching with reference to FL requirements in colleges and universities. A report for the LAS Committee on the Foreign Language Requirement, the University of Illinois, Urbana.

Johnson, T.R., and K. Krug. 1980. Integrative and instrumental motivations: in search of a measure. In Research in Language Testing, eds. J.W. Oller, Jr. and K. Perkins, pp. 241 – 249. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House.

Krashen, S.D. 1980. The input hypothesis. In Current Issues in Bilingual Education: Proceedings of the Georgetown Round Table on Languages and Linguistics, ed. J.E. Alatis, pp. 168 – 180. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown.

Krashen, S.D. 1985. The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. New York: Longman.

Lukmani, Y. 1972. Motivation to learn and language proficiency. Language Learning 22: 261 – 274.

Ogawa, G., M. Byler, and J.W. Oller, Jr. 1981. Pandora’s box revisited in Spanish-speaking subjects. Working Paper. Linguistics Department, University of New Mexico.

Oller, J.W., Jr. 1977. Affective variables in second language acquisition: how important are they? In Papers in ESL, NAFSA, ed. B.W. Robinett, pp. 7 – 12. Washington, D.C.: National Association for Foreign Student Affairs.

Oller, J.W., Jr., and K. Perkins. 1978. Language proficiency as a source of variance in self-reported affective variables. In Language in Education: Testing the Tests, eds. J.W. Oller, Jr. and K. Perkins, pp. 103 – 125. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House.

Oller, J.W., Jr., L. Baca, and F. Vigil. 1977. Attitudes and attained proficiency in ESL: a sociolinguistic study of Mexican-Americans in the southwest. TESOL Quarterly 11: 173 – 183.

Oller, J.W., Jr., A.J. Hudson, and P.F. Liu. 1977. Attitudes and attained proficiency in ESL: a sociolinguistic study of native speakers of Chinese in the United States. Language Learning 27: 1 – 27.

Oller, J.W., Jr., K. Prapphal, and M. Byler. 1982. Measuring Affective Factors in Language Learning. Singapore: SEAMEO Regional Language Centre.

Prapphal, K., J.W. Oller, Jr., Kuang-Hsiung Yu, Steven Ross, and M. Byler. 1982.Nonprimary language acquisition: a cross-cultural study. Paper presented at the Sixteenth TESOL Convention, May 4, Honolulu.

Notes

1 The data are taken from Ogawa,

Byler and Oller (1981), and Prapphal,

Oller, Yu, Ross, and

Byler (1982).

2 The original version of the questionnaire consists of three parts: Instrumentality, Integrativeness, and Willingness-to-Work. There are 36 propositions, 72 “direct” and 36 “indirect”, 108 items in all.

3 Although the repeated-measurement technique shows consistency of responses, problems concerning the approval motive, self-flattery, and response set still remain.