Some Factors in Learning English in Thailand

Kanchana Prapphal and John

W. Oller, Jr.

University of New Mexico

U.S.A.

To design an optimally efficient EFL curriculum, it is necessary to investigate factors which may obstruct or enhance the acquisition of the nonprimary language. It was found that affective variables and formal exposure were not good predictors of EFL proficiency of Thai first-year university students. The causal model, hypothesizing that demographic variables may cause certain attitudes towards English which may in turn affect the attainment of English proficiency, was consistent with the data although the observed relationships were weak.

Affective variables are believed to be substantially related to language acquisition. Dulay and Burt (1977) called unfavorable attitudes “socio-affective filters”. They are believed to obstruct input to the language acquisition device. Krashen (1980) postulated the “Input Hypothesis” and referred to affective filters as factors which inhibit comprehensible input. Language learners tend to acquire the target language if affective filters are down. If the filters are up, potential input may not be fully utilized and acquisition will be obstructed.

Krashen (1981) distinguished learning from acquisition. In his theory, informal exposure or implicit learning is related to language acquisition while formal exposure or explicit learning is more closely related to learning. Evidence for such a distinction was reported by Mason (1971), Schumann (1978), Monshi-Tousi, Hossenine-Fatemi and Oller (1980), Oller, Perkins and Murakami (1980), Palmer (in press), and Ogawa, Byler, Oller and Prapphal (in press).

This study attempts to answer the following questions:

(1) Are affective variables and demographic variables (formal exposure, high school GPA, and SES) good predictors of attained English proficiency of Thai first-year university students?

(2) Is there a possible causal connection between demographic (experiential) background, affective variables, and knowledge of English?

(3) What is the nature of the underlying dimensions of the mentioned relationships?

Subjects

The subjects were 528 freshmen from thirteen academic fields at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok, Thailand. Most of the students had studied English as a foreign language in formal exposure through a structural approach for about ten years.

Materials

The Criterion

The sum of the standardized scores of two English language cloze tests and the Michigan Test of English Language Proficiency (Form K) was used as the criterion. Each cloze test consisted of a 250-word passage with every fifth word deleted. There were 50 deleted items for each test. One passage was chosen from social science and the other from physical science. The tests were scored by the contextually-appropriate method. The Michigan Test was comprised of three parts: Grammatical Usage, Vocabulary, and Reading Comprehension. There were 40 multiple-choice items for the first two parts and 20 items for the last.

Predictors

Demographic variables. Information on socioeconomic background, high school GPA, and formal exposure (number of years of English study) was asked for in the first part of the Questionnaire on Attitudes towards English.

Affective variables. The triple correlation technique was built into the Questionnaire on Attitudes towards English to check internal consistency of the responses of the subjects. The Questionnaire consisted of three parts: Instrumentality, Integrativeness, and Willingness-to-Work. These were based on Gardner and Lambert’s (1972) instrumental and integrative orientations, and Jakobovits’s (1970) perseverance. The measure proved to be reliable and tending towards validity. See Prapphal, Oller and Byler (1982) for the details of the design and statistical results for reliability and validity of the Questionnaire.

Data Analysis and Results

The analysis was carried out in three steps through investigation of:

(1) the magnitude of the relationships

between linguistic factor (English proficiency) and nonlinguistic factors

(formal exposure, high school GPA, SES, and affective variables),

(2) the hypothesized causal explanations,

and

(3) the underlying dimensions

of the relationships.

Magnitude of the Relationships

A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed with demographic variables (SES, Formal Exposure, and High School GPA) entered first, attitudes towards English (Instrumentality, Integrativeness, and Willingness-to-Work) second, and the interaction last. The order was determined based on the hypothesis that previous experience or demographic information may causally affect attitudes towards English, which in turn will affect EFL proficiency. Each variable was tested controlling for the variables that were entered in that step and for those in previous steps. Table 1 presents the results from a multiple regression analysis.

The overall F ratio indicated that the regression of English proficiency on demographic variables, attitudes, and their interaction was statistically significant, accounting for 35% of the variance (F = 10.047, df = 19,359, p ? .001, R2 = .347). Investigation of the relationship between demographic variables and English proficiency revealed that demographic variables were significantly related to English proficiency accounting for 29% of the variance (F = 39.975, df = 4,359, p ? .001, R2 = .291).

When testing the effect of each demographic variable (controlling for other demographic variables), Formal Exposure was positively and significantly related to the criterion but accounted for only 1% of its variance (F = 7.509, df = 1,359, p ? .01, R2 = .014). High School GPA was positively and significantly related to the measure, accounting for 22% of the variance (F = 119.672, df = 1,359, p ? .001, R2 = .218). Father’s Income was also positively and significantly related to knowledge of English but accounted for only 2% of the variance (F = 9.358, df = 1,359, p ? .01, R2 = .017). Mother’s Income was not separately and significantly related to the dependent variable.

When testing the relationships between attitudes towards English and the

attainment of English proficiency controlling for demographic variables,

attitudes were significantly related to English proficiency but accounted

for only 4% of the variance (F = 7.419, df = 3,359, p ? .001, R2 = .040).

When Instrumentality and Integrativeness were controlled, Willingness-to-Work

was positively and significantly related to English proficiency but accounted

for a little less than 2% of the variance. Integrativeness and Instrumentality

by themselves were not significantly related to the criterion. The

interaction between demographic information and attitudes with English

proficiency was also not significant.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Willingness-to-Work |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| **p<.01 ***p<.001 |

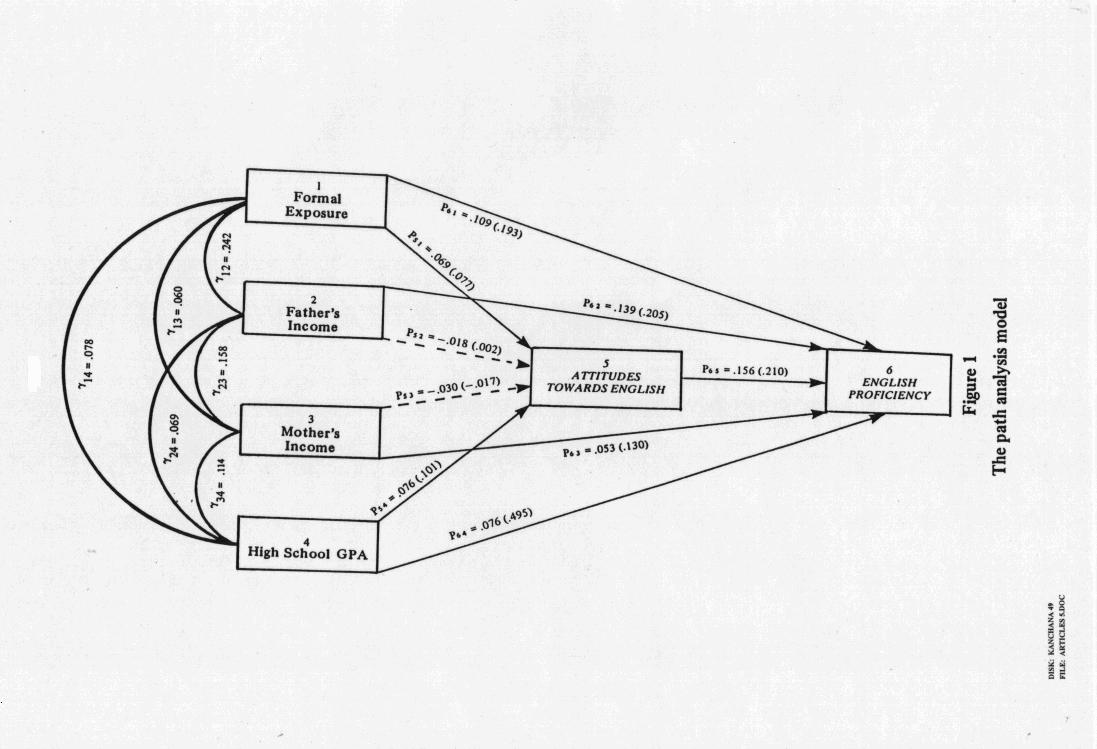

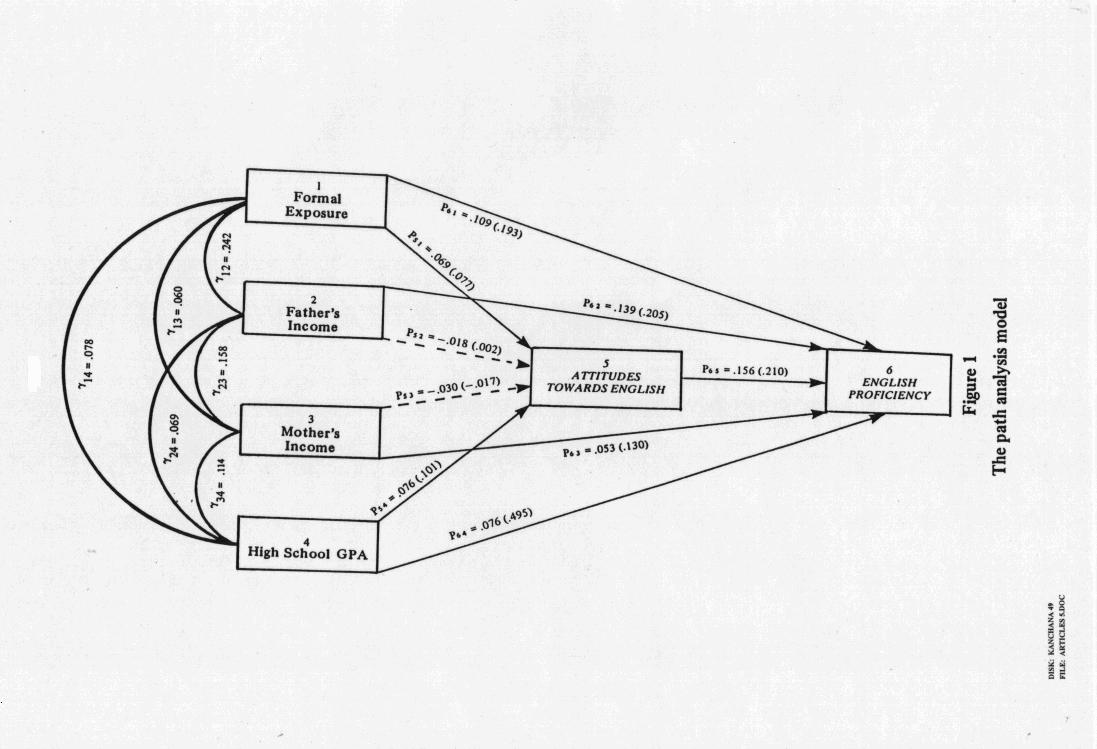

Path analysis was carried out to examine a possible causal relationship

between demographic variables, attitudes towards English, and English proficiency

mentioned in the previous section. The three attitudes scores (Instrumentality,

Integrativeness, and Willingness-to-Work) were added together to form one

affective score. Figure 1 represents the path diagram of the postulated

relationships.

Path coefficients of less than .05 were considered meaningless and should be discarded from the model. This was the case for P52 and P53. This means that Father’s Income and Mother’s Income were not causally related to English proficiency for this population. Although the data was consistent with the path model, the causal relationships were weak except for High School GPA.

Underlying Dimensions of the Relationships

A post-hoc principal components analysis (number of factors set at three) was performed on demographic variables, attitudes towards English, and English proficiency. The varimax rotated factor matrix showing the distribution of the variables over three factors is given in Table 2.

The factor matrix showed that Factor 1 included High School GPA, the Michigan

and Cloze Tests. The loadings of these variables on this factor ranged

from .65 to .87. This factor was labeled a cognitive factor.

The following variables loaded heavily on the second factor: Instrumentality

(.843), Integrativeness (.885), and Willingness-to-Work (.860). This

second factor was identified with affective constructs so it was named

an affective factor. The demographic variables received heaviest

loadings on Factor 3. Father’s Income weighted most heavily at .766.

Next was Formal Exposure at .667, and finally Mother’s Income at .489.

This factor was called a demographic factor.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Demographic Variables

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cloze | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Since High School GPA explains most of the reliable variance in EFL proficiency, it may be concluded that a cognitive factor plays a major role for this population. Formal exposure to English is not a good predictor of language performance. This suggests that the previous English language experience of these subjects has not resulted in much of what Krashen (1980, 1981) calls “acquisition”. It has also been suggested (Krashen, personal communication) that positive attitudes towards English may not be fostered in the contexts of formal exposure.

These conclusions are supported by the path analysis in Figure 1.

The model hypothesizing that demographic variables may cause certain attitudes

towards English, which in turn may affect EFL proficiency of Thai students

is consistent with the data. Nevertheless, only High School GPA indicates

a moderately strong relationship with English proficiency calling into

question the causality of other factors.

References

Dulay, H.C. and Burt, M. 1977. Remarks on creativity in

language acquisition.

Viewpoints on English as a

second language, ed. by M. Burt, H. Dulay and M. Finocchiaro.

New York: Regents.

Gardner, R.C. and Lambert, W.E. 1972. Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House.

Jakobovits, L.A. 1970. Foreign language learning: a psycholinguistic analysis of the issues. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House.

Krashen, S. 1980. The input hypothesis. Current issues in bilingual education: proceedings of the Georgetown Round Table on Languages and Linguistics, ed. by J.E. Alatis. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown.

____________. 1981. Second language acquisition and second language learning. New York: Pergamon Press.

Mason, C. 1971. The relevance of intensive training in English as a foreign language for university students. Language learning 21. 197 – 204.

Monshi-Tousi, M., Hosseine-Fatemi, A. and Oller, J.W., Jr. 1980. English proficiency and factors in its attainment: a case study of Iranians in the United States. TESOL Quarterly 14. 365 – 37.

Ogawa, G., Byler, M., Prapphal, K. and Oller, J.W., Jr. Pandora’s box revisited in Spanish speaking subjects. In press.

Oller, J.W., Jr., Perkins, K. and Murakami, M. 1980. Seven types of learner variables in relation to ESL learning. Research in language testing, ed. by J.W. Oller, Jr. and K. Perkins. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House.

Palmer, A.S. Compartmentalized and integrated control. Issues in language testing reasearch, ed. by J.W. Oller, Jr. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House. In press.

Prapphal, K., Oller, J.W., Jr. and Byler, M. 1982. Measuring affective factors in language learning. Occasional Papers No. 19. Singapore: SEAMEO Regional Language Centre.

Schumann, J.H. 1978. The acculturation model for second-language

acquisition. Second-language acquisition and foreign language

teaching, ed. by R.C. Gingras. Washington, D.C.: Center

for Applied Linguistics.