Faculty of Arts,

Chulalongkorn University

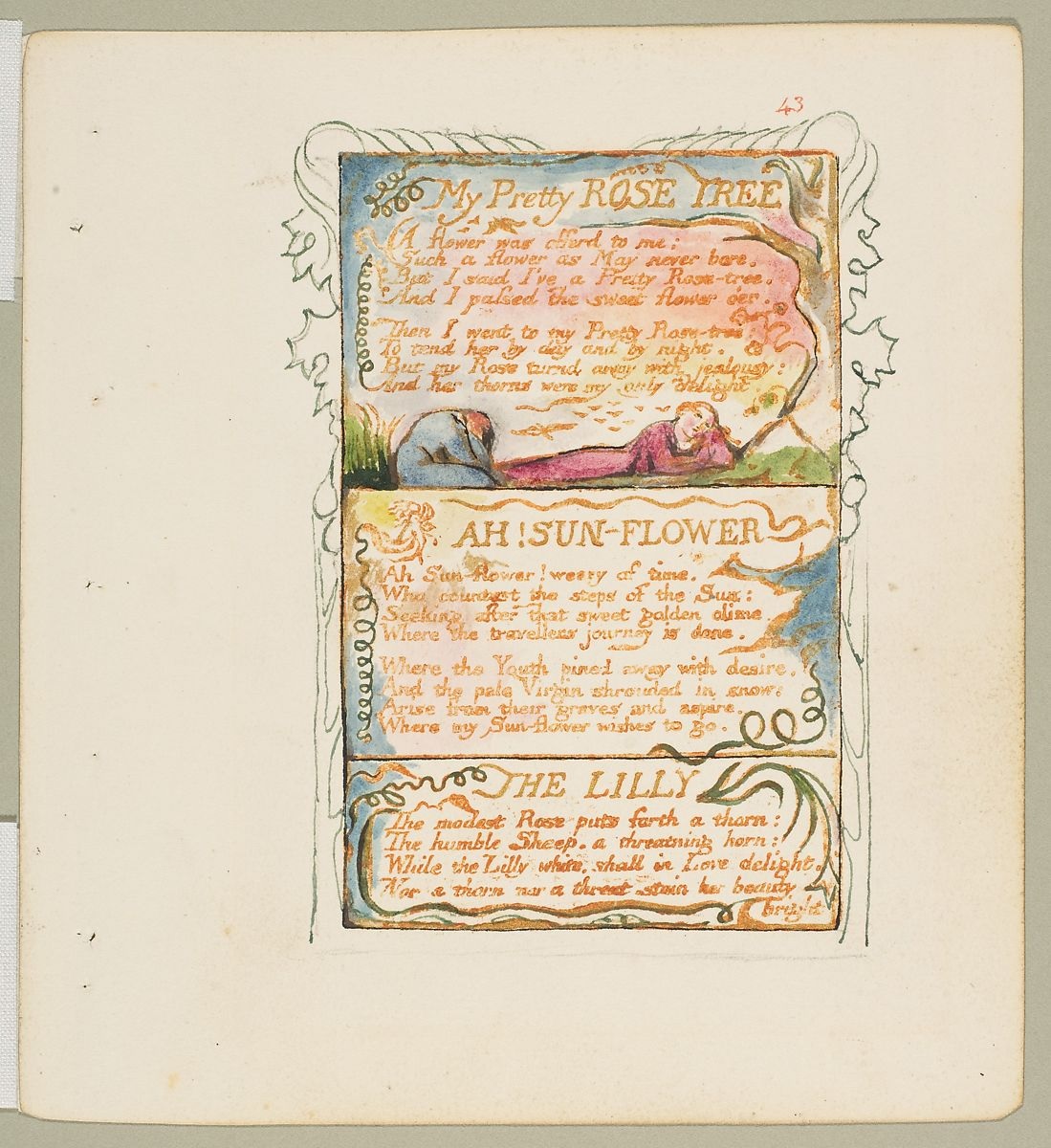

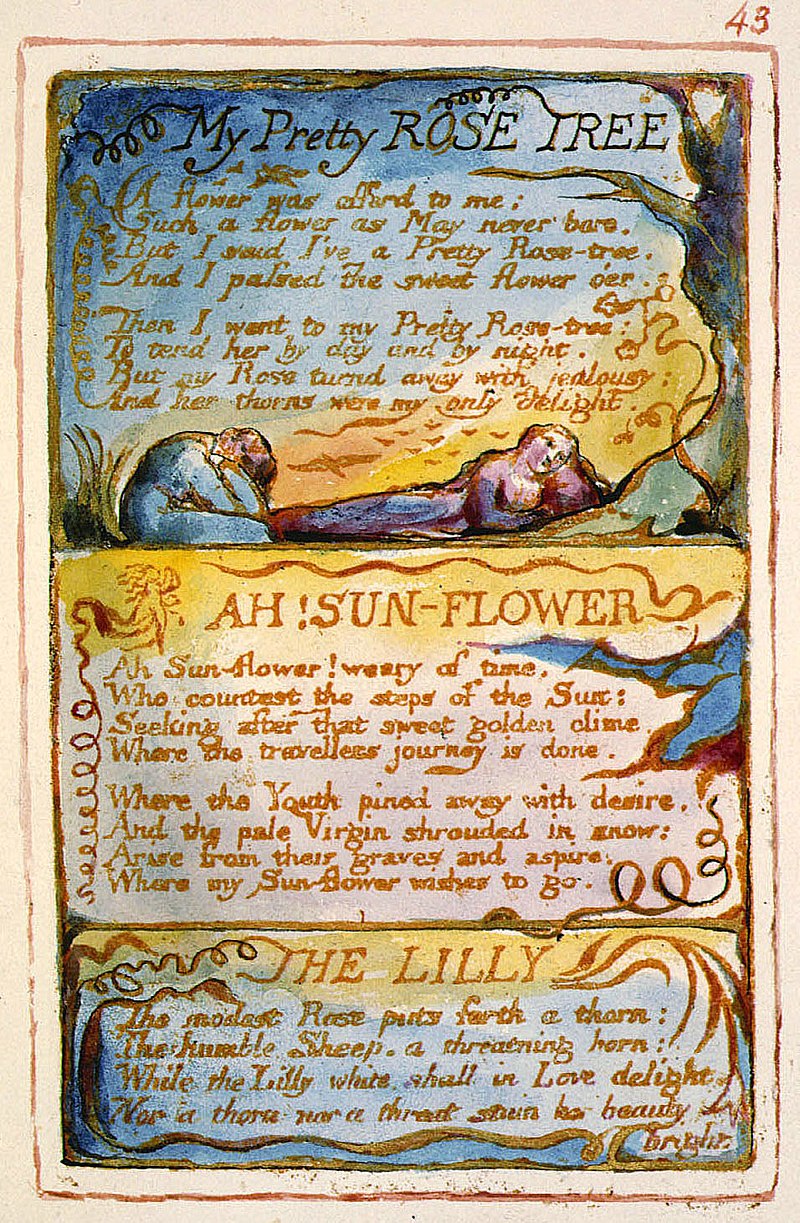

"My

Pretty Rose Tree"

(1794)

William Blake

(November

28, 1757

– August 12, 1827)

|

Copy

A, Plate 33

|

A flower was

offered to me;

Such a flower as May never bore

But I said I've a Pretty Rose-tree:

And I passed the sweet flower o'er.

Then I went to my Pretty rose-tree;

To tend her by day and by night.

But my Rose turnd away with jealousy:

And her thorns were my only delight. |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

"My Pretty Rose Tree" Notes

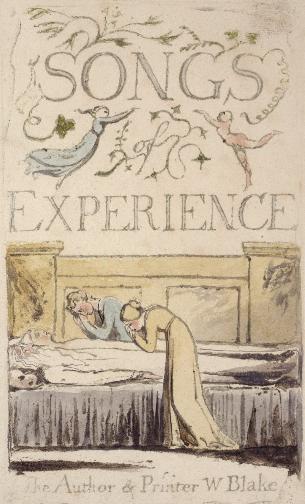

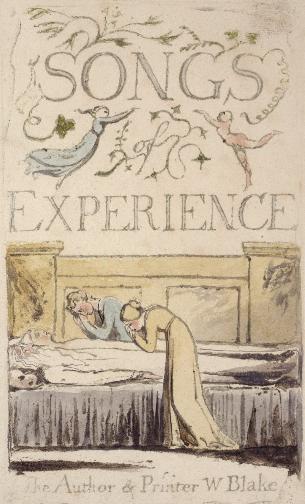

This poem is in the Songs of

Experience section of Songs of

Innocence and of Experience: Shewing the Two Contrary States of the

Human Soul (1789).

4 passed...o'er:

passed over

- pass over (Oxford

Dictionary)

phrasal verb

1 (pass someone over, pass over someone) Ignore the claims of

someone to promotion or advancement.

1.1 (pass something over, pass over something) Avoid mentioning

or considering something.

7 jealousy:

- jealous (Oxford

Dictionary)

adjective

1 Feeling or showing an envious resentment of someone or their

achievements, possessions, or perceived advantages.

‘she was always jealous of me’

1.1 Feeling or showing a resentful suspicion that one's partner

is attracted to or involved with someone else.

‘a jealous husband’

1.2 Fiercely protective of one's rights or possessions.

‘the men were proud of their achievements and jealous of their

independence’

1.3 (of God) demanding faithfulness and exclusive worship.

‘In Hebrews we also meet the strong protests of the jealous God,

who is intolerant of rivals with a holy intolerance.’

8 delight:

- delight (Oxford

Dictionary)

1 Great pleasure.

‘the little girls squealed with delight’

1.1 (count noun) A cause or source of great pleasure.

‘the trees here are a delight’

- delight (Etymology

Online)

c. 1200, delit, "high degree of pleasure or satisfaction," also

"that which gives great pleasure," from Old French delit "pleasure,

delight, sexual desire," from delitier "please greatly, charm,"

from Latin delectare "to allure, delight, charm, please,"

frequentative of delicere "entice" (see delicious). Spelled delite

until 16c.; the modern unetymological form is by influence of light,

flight, etc.

Prose

Paraphrase

| Blake's

Poem |

Prose

Paraphrase |

Some

Interpretation |

Comments

|

|

A flower was offered to me;

Such a flower as May never bore

|

A flower was offered to me. The month of May has

never produced a flower like this.

|

A flower was offered to me. A beautiful flower like

this the month of May, the height of spring, has never

created.

|

How important is the inversion in the original? Does

May replacing the flower affect the focus of the lines?

What kind of flower is this that does not bloom naturally in

spring?

|

But I said I've a Pretty Rose-tree:

And I passed the sweet flower o'er.

|

But I said that I have a pretty rose tree, and I did

not accept the sweet flower.

|

But I said that I have a pretty rose tree, and I did

not consider taking the sweet flower.

|

How important is the conjunction "and"? How does

reading it as "so" alter Blake's text?

|

Then I went to my Pretty Rose-tree;

To tend her by day and by night.

|

Then I went to my pretty rose tree to tend her during

the day and at night. |

Then I went back to my pretty rose tree to take care

of her day and night. |

How significant is the possessive?

How significant is the gendered pronoun?

|

But my Rose turnd away with jealousy:

And her thorns were my only delight.

|

But my rose turned away with jealousy and her thorns

were my only enjoyment.

|

But my rose, out of jealousy, did not bloom and I can

only enjoy her thorns.

|

How important is the transition from "Rose-tree" to

"Rose" in these last lines?

What resonance does the possessive "my" have at the end? What

sense does each "my" have? Are they the same?

|

The Songs of Innocence

are indeed "of" and not "about" the state of innocence. There is much

critical debate about Blake's Innocence,

and little that is definitive can be said about it. The reader should know

that the root meaning of innocence is "harmlessness," the derived meanings

"guiltlessness" and "freedom from sin." But Blake uses the word to mean

"inexperience" as well, which is a very different matter. As the contrary of

Experience, Innocence cannot be reconciled with it within the context of

natural existence. Implicit in the contrast between the two states is a

distinction Blake made between "unorganized innocence," unable to sustain

experience, and an organized kind which could. On the manuscript of The

Four Zoas, he jotted down: "Unorganized

Innocence: An Impossibility. Innocence dwells with Wisdom, but

never with Ignorance."

Since Innocence and Experience are states of the soul

through which we pass, neither is a finality, both are necessary, and

neither is wholly preferable to the other. Not only are they satires upon

one another, but they exist in cyclic relation as well. Blake does not

intend us to see Innocence as belonging to childhood and Experience to

adulthood, which would be not only untrue but also uninteresting. [...]

Innocence satirizes Experience just as intensely as it itself is satirized

by Experience, and also...any song of either state is also a kind of satire

upon itself.

--Harold Bloom and Lionel Trilling, "Songs

of Innocence and of Experience," Romantic

Poetry and Prose (New York: OUP, 1973): 17–18.

"Read patiently take not up this Book in an idle hour the consideration of

these things is the whole duty of man & the affairs of life & death

trifles sports of time these considerations business of Eternity." Blake's

annotations to a volume he studied in 1798 (see Blake, ed. Erdman

[E] 611) can serve today to characterize the attention deserved and

significance offered by the most familiar work of England's "last great

religious poet" (Ackroyd 18) and "greatest revolutionary artist" (Eagleton,

in Larrissy ix).

[...]

"Language is the house of Being,"

according to Heidegger's famous figure (see Steiner 127) but for Blake, as

for Wordsworth, that structure becomes for most a prison-house maintained

by "pre-established codes," by cliché and convention. The warden of the

prison-house, the fashioner of "mind-forgd manacles," the force that has

barred us from the play of Being in language, as from the stunning energy

of true poetry, can be seen as "the bard." The fallacy in crediting such

assumed authority looms in the "Introduction" to Songs

of Experience, where, by the eighth line, three distinct subjects

"might controll / The starry pole." With its echoes of Jeremiah ("O earth,

earth, earth, hear the word of the Lord") and the God of Paradise

Lost ("past, present, future he beholds"), the bard seems to

command reverence—but as in other cases, on inspection, the compelling

language breaks into mumbo jumbo, etched on a plate whose vista of stars

is graphically barred by the cloud of words. Students of the Bible, and of

Wesley's great hymn, "Wrestling Jacob," will recognize that it is the

opportunity to struggle for blessing or interpretation from a sacred

messenger that is given "till the break of day." The religious references

resonate with the particularly eighteenth-century, evangelical sense of

"experience" as the inner history of one's religious emotion (see OED,

s.v., 4b)—indeed, "hymn of experience" appears throughout accounts of

Methodism.

--Nelson

Hilton, "William

Blake, Songs of Innocence and of Experience," The

Blackwell Companion to Romanticism, ed. Duncan Wu (Oxford:

Blackwell, 1998)

|

|

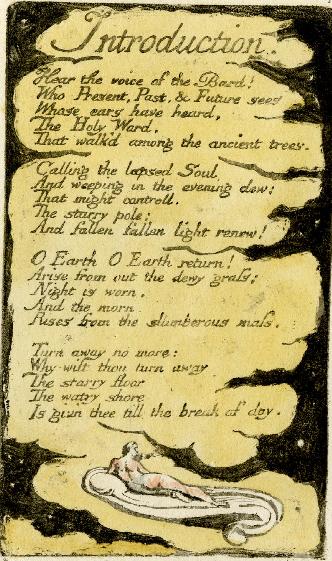

"Introduction," Songs

of Experience (1789)

Hear the voice of the Bard!

Who Present, Past, & Future sees

Whose ears have heard,

The Holy Word,

That walk'd among the ancient trees.

Calling the lapsed Soul

And weeping in the evening dew:

That might controll,

The starry pole;

And fallen fallen light renew!

O Earth O Earth return!

Arise from out the dewy grass;

Night is worn,

And the morn

Rises from the slumberous mass.

Turn away no more:

Why wilt thou turn away

The starry floor

The watry shore

Is giv'n thee till the break of day.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20 |

This persona is not Blake.

cf. Genesis

3:8

cf. Jeremiah

22:29

|

|

Study Questions

- How

many characters do you see in the poem?

- What

difference does Blake make between a flower and a tree?

- What

difference does Blake show between the flower and the

rose?

- What

distinction does Blake make between "sweet" and

"pretty"?

- Consider

the two-stanza structure of the poem. Is this reflected

in the illumination? Why or why not?

- What

connection is there between the possessive diction and

the word jealousy?

- How

do the two buts connect and/or contrast the last

two lines of each stanza?

- What

value assumption is the speaker making when he/she

refuses the gift of the flower and how does his

disrupted assumption at the end change that value

concept?

|

Sample Student

Responses to William Blake's "My Pretty Rose Tree"

Response 1:

Study Question:

|

|

Student Name

2202234

Introduction to the Study of English Literature

Acharn Puckpan

Tipayamontri

June 12, 2013

Reading

Response 1

Title

Text.

|

|

Plates

|

|

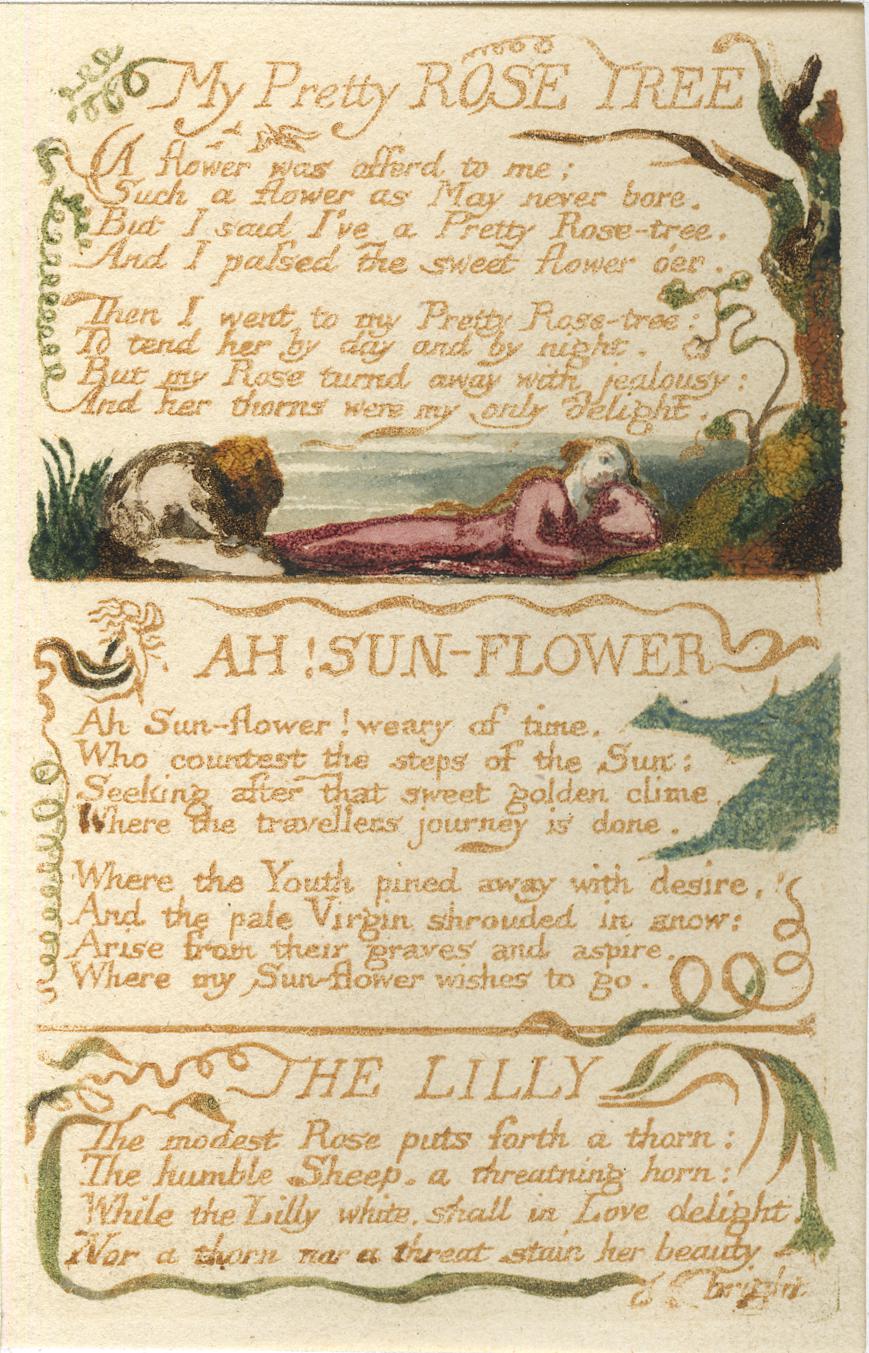

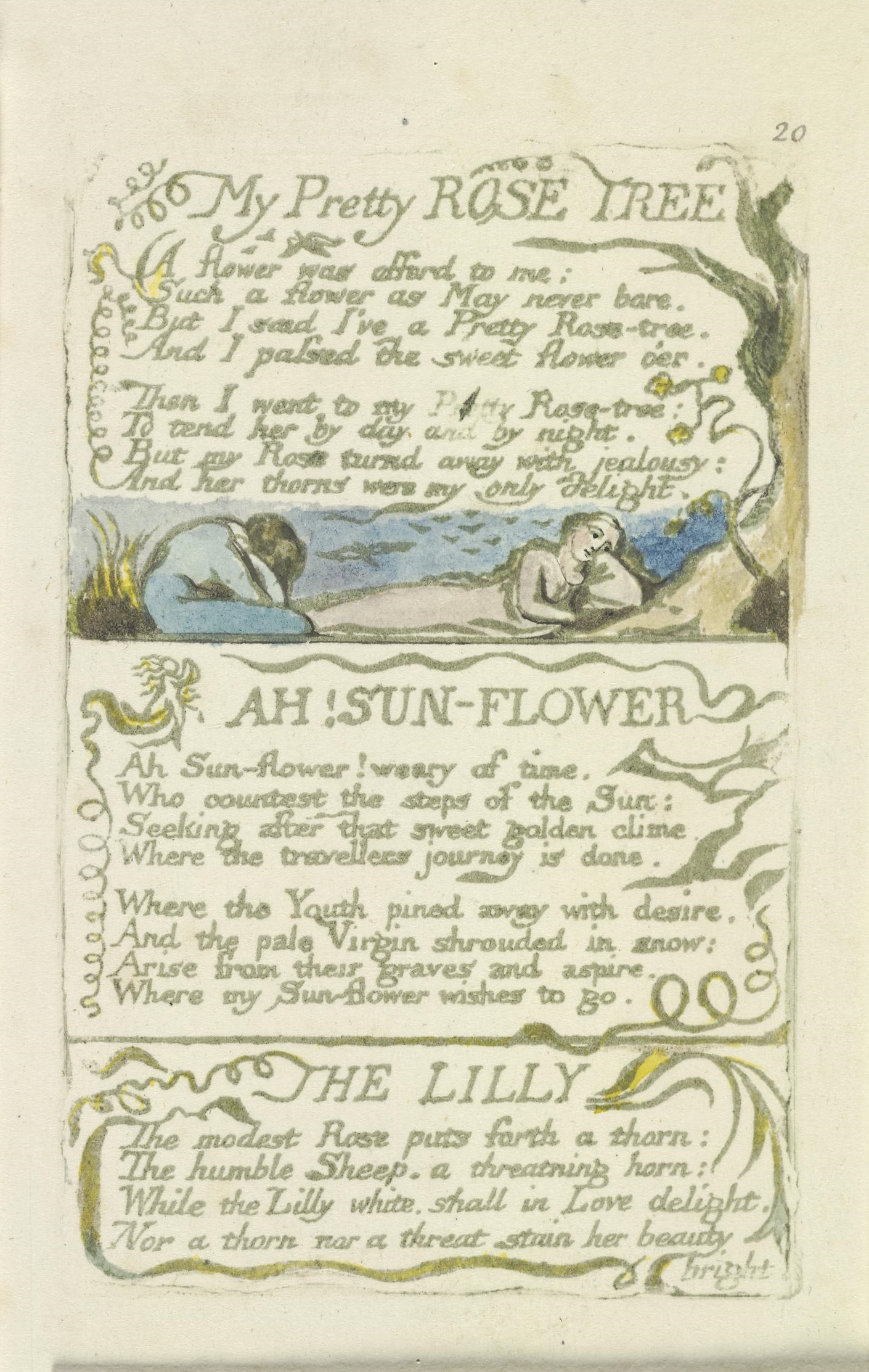

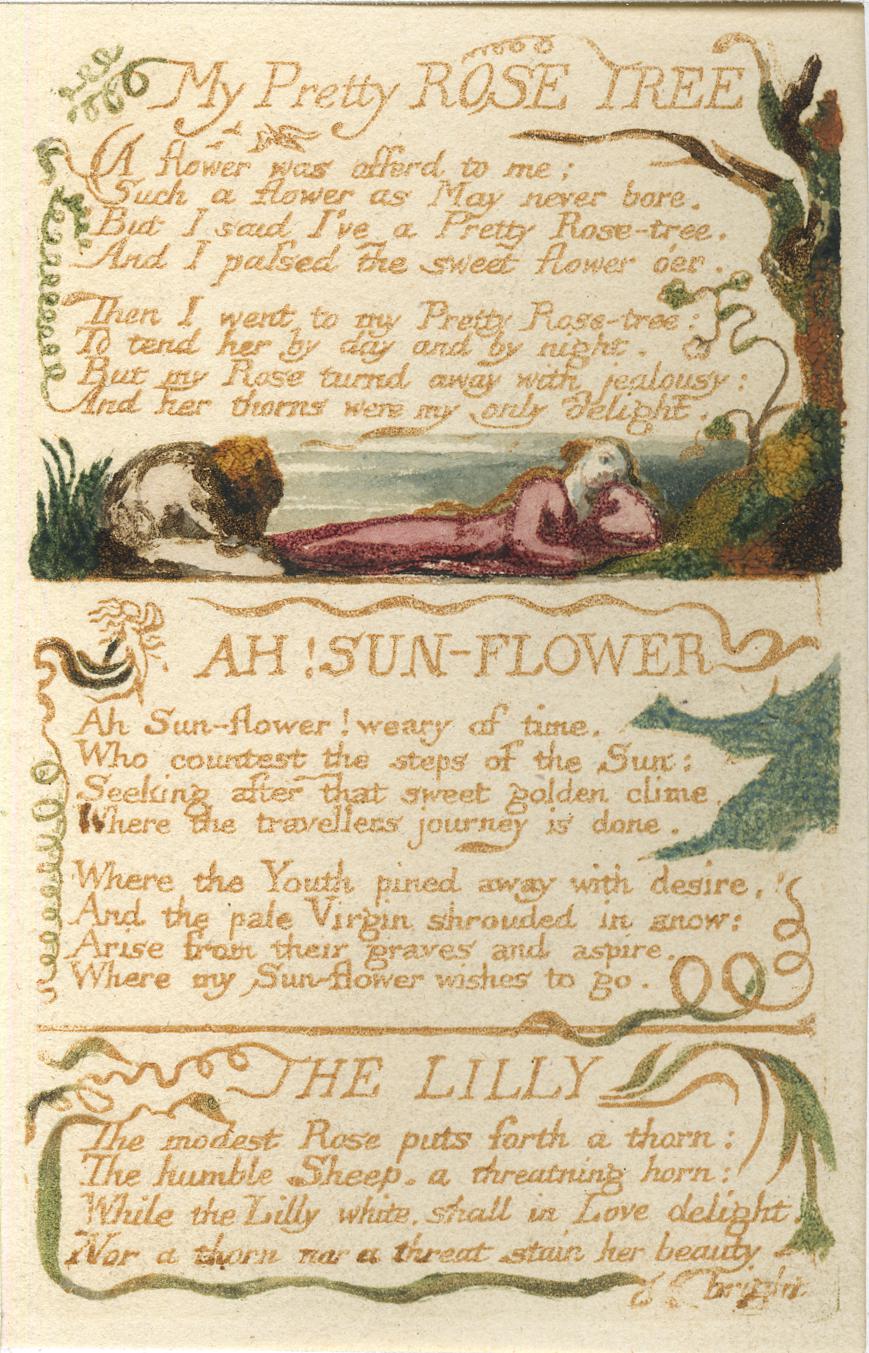

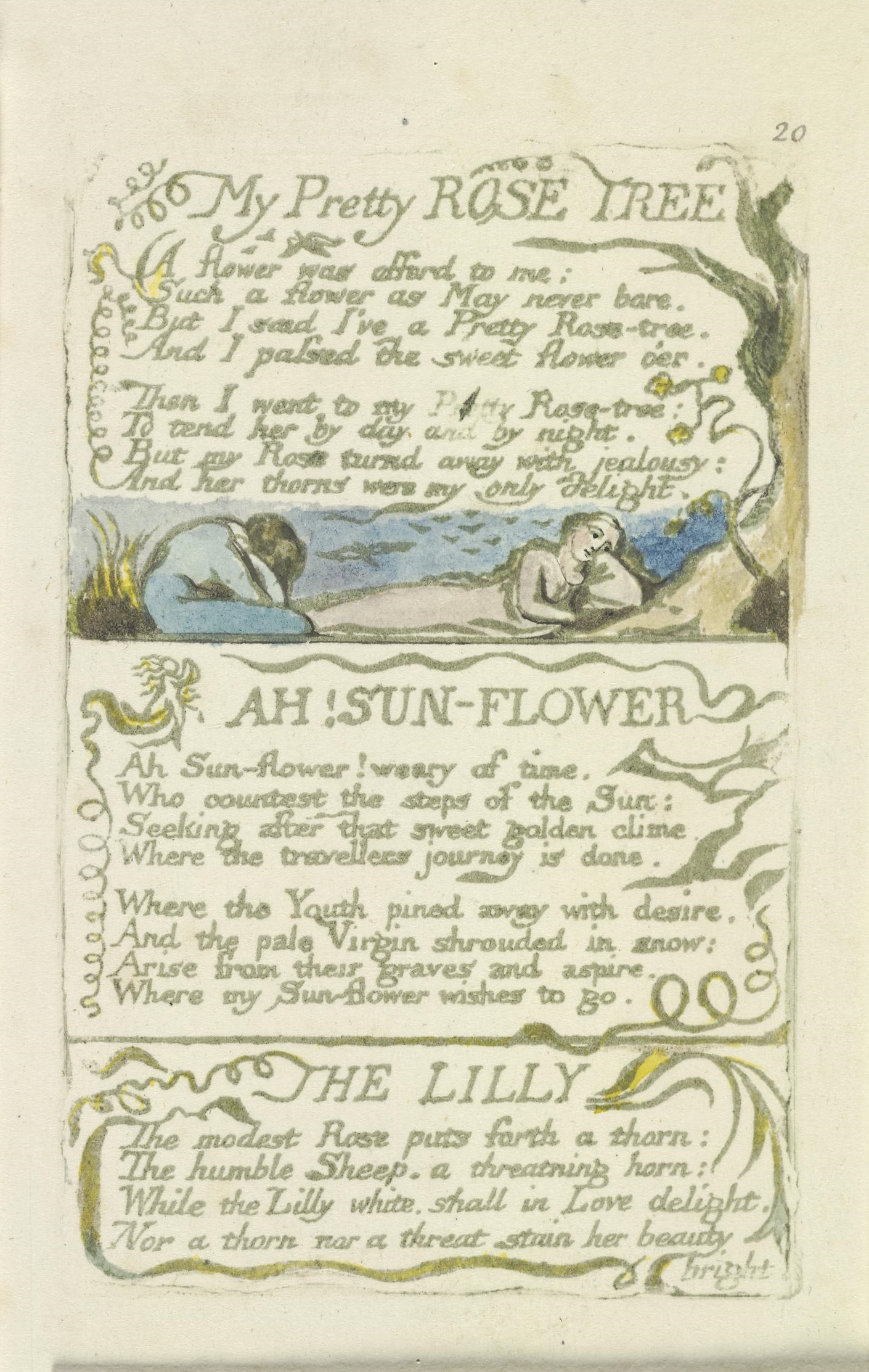

- Blake, William. "My Pretty Rose Tree." 1794. Songs

of Experience. Plate 43. Copy T. The British

Museum.

|

|

- Blake, William. "My Pretty Rose Tree." 1794. Songs

of Experience. Plate 50. Copy A. The British

Museum.

|

|

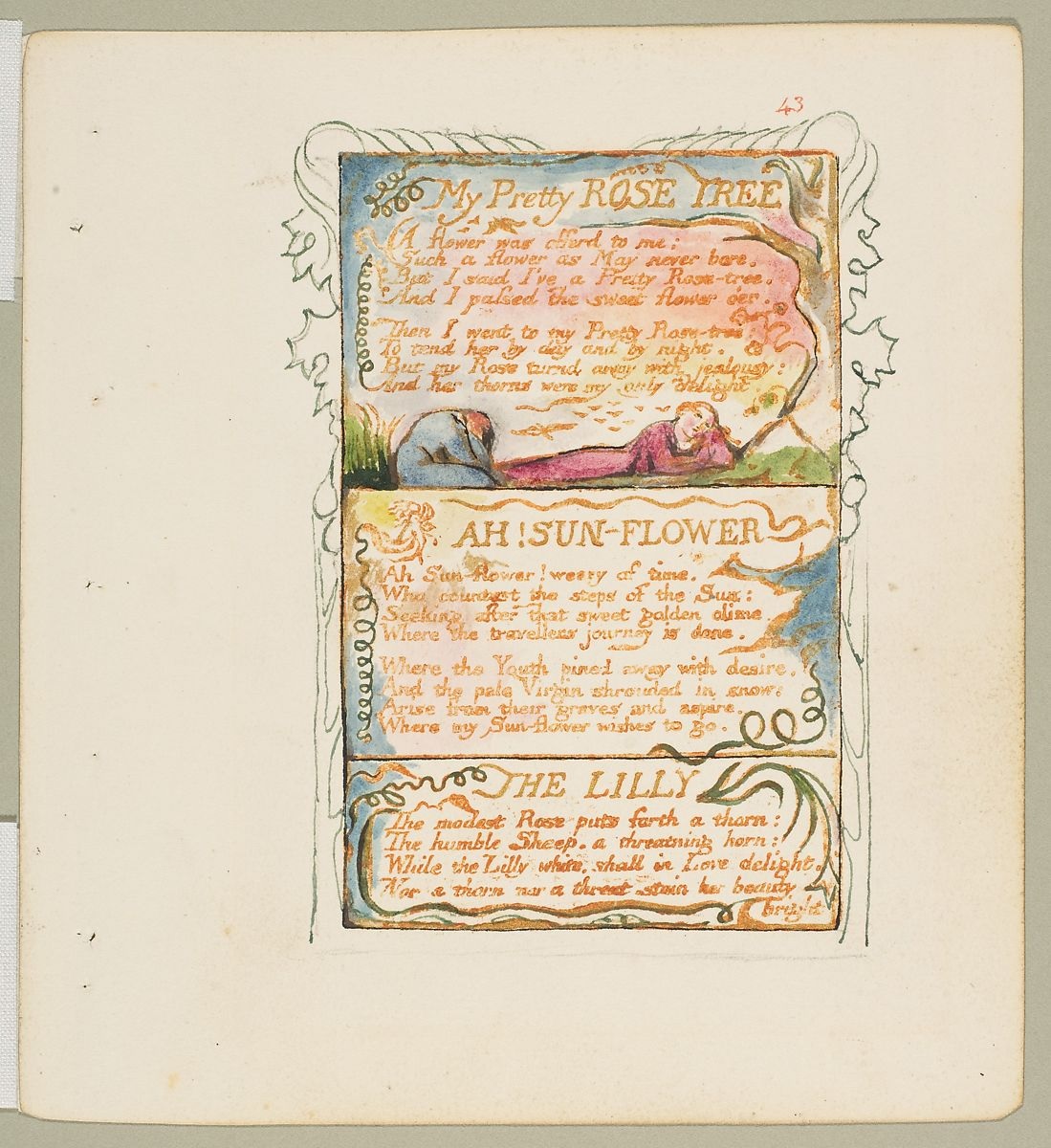

- Blake, William. "My Pretty Rose Tree." c. 1825. Songs of Experience.

Plate 43. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

|

|

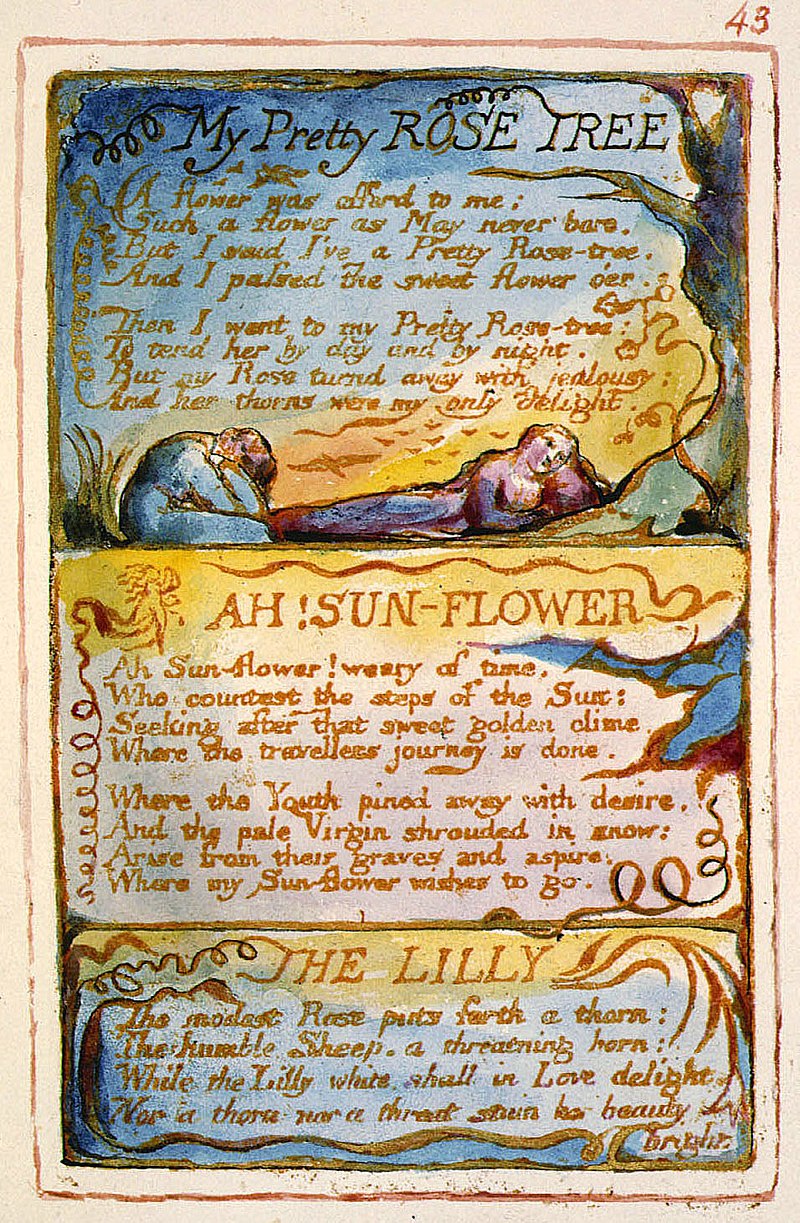

- Blake, William. "My Pretty Rose Tree." 1826. Songs

of Innocence and Experience. Object 43. Copy AA.

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

|

Media

|

|

- Colin Harrison,

"William Blake: Visionary," Ashmolean Museum

(2015; 2:03 min.)

|

|

- "William Blake's

Printing Process," The British Library (2014; 8:09

min.)

|

|

- Peter Ackroyd, The Romantics,

BBC (2006; video clips)

- Episode 1: Liberty (59:02 min.; Blake,

Coleridge, Wordsworth)

- Episode 2: Nature (58:07 min.; Mary Shelley)

- Episode 3: Eternity (59:00 min.; Byron,

Keats, Shelley)

|

|

- "William Blake," Famous Authors,

directed by Malcolm Hossick, Academy Media (2005; 31:22

min.)

|

Reference

Blake, William. The Complete

Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Edited by David V. Erdman,

Anchor, 1988.

Mitchell, W. J. T. Blake's

Composite Art: A Study of the Illuminated Poetry. Princeton UP,

1978.

Further Reading

Keynes, Geoffrey. Drawings of

William Blake: 92 Pencil Studies. Dover, 1970.

Lister, Raymond. The

Paintings of William Blake. Cambridge UP, 1986.

Home | Literary

Terms

Last updated August 17, 2020