Faculty of Arts,

Chulalongkorn University

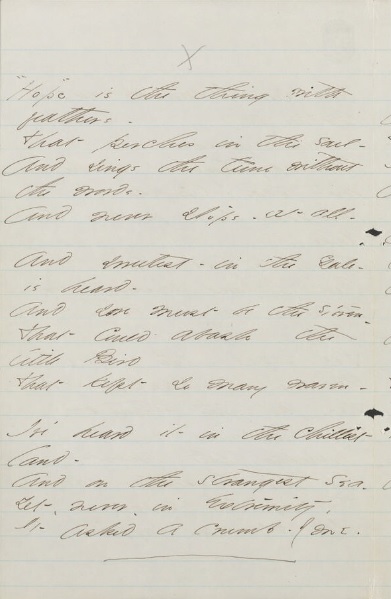

"Hope is the thing with feathers—"

(1890)

Emily

Dickinson

(December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886)

Hope

is the thing with feathers –

|

|

That

perches in the soul –

|

|

And

sings the tune without the words –

|

|

And never stops at all –

|

|

|

|

And

sweetest – in the Gale – is heard –

|

5

|

And sore must be the storm –

|

|

That could abash the little Bird

|

|

That

kept so many warm –

|

|

|

|

| I've heard it in the chillest land – |

|

| And on the strangest Sea – |

10

|

| Yet – never – in Extremity, |

|

| It asked a crumb – of me. |

|

Notes

7 abash: discompose, shake

- abash (Merriam-Webster)

transitive verb

to destroy the self-possession or self-confidence of (someone):

disconcert

He had never blushed in his life; no humiliation could abash him.—

Charlotte Brontë

- abash (Online

Etymology Dictionary)

"perplex or embarrass by suddenly exciting the conscience, discomfit,

make ashamed," late 14c., earlier "lose one's composure, be upset"

(early 14c.), from Old French esbaiss-, present stem of esbaer

"lose one's composure, be startled, be stunned."

Originally, to put to confusion from any strong emotion, whether of

fear, of wonder, shame, or admiration, but restricted in modern times to

effect of shame. [Hensleigh Wedgwood, "A Dictionary of English

Etymology," 1859]

The first element is es "out" (from Latin ex; see ex-). The

second may be ba(y)er "to be open, gape" (if the

notion is "gaping with astonishment"), possibly ultimately imitative of

opening the lips.

11 in

Extremity:

- extremity

- extremity (Merriam-Webster)

1 a: the farthest or most remote part, section, or point

the island's westernmost extremity

b: a limb of the body especially: a human hand or foot

2 a: extreme danger or critical need

b: a moment marked by imminent destruction or death

3 a: an intense degree

the extremity of his participation — Saturday Rev.

b: the utmost degree (as of emotion or pain)

The extremity of her grief is impossible to imagine,

4: a drastic or desperate act or measure

driven to extremities

made offers of aid to the refugees, and of asylum in extremity

- extremity (Oxford

Dictionary)

1 The furthest point or limit of something.

‘the peninsula's western extremity’

1.1 (extremities) The hands and feet.

‘tingling and numbness in the extremities’

2 mass noun The degree to which something is extreme.

‘the extremity of the violence concerns us’

2.1 A condition of extreme adversity.

‘the terror of an animal in extremity’

- extremity (Online

Etymology Dictionary)

late 14c., "one of two things at the extreme ends of a scale," from

Old French estremite (13c.), from Latin extremitatem (nominative

extremitas) "the end of a thing," from extremus "outermost;"

see extreme

(adj.), the etymological sense of which is better preserved in this

word. Meaning "utmost point or end" is from c. 1400; meaning "limb or

organ of locomotion, appendage" is from early 15c. (compare extremities). Meaning "highest degree" of

anything is early 15c.

- in extremis

- in extremis (Merriam-Webster)

in extreme circumstances

especially: at the point of death

They are helping a family in extremis.

- in extremis (Oxford Dictionary)

1 In an extremely difficult situation.

‘one or two would talk to the press in extremis’

1.1 At the point of death.

‘cannibalism is rare but, in extremis, it is something to

which the human species will resort’

- in extremis (Online Etymology Dictionary)

"at the point of death," 16c., Latin, literally "in the farthest

reaches," from ablative plural of extremus "extreme"

What

was the United States like that Whitman and Dickinson were born into?

Source: Ed

Folsom, Selected American Authors: Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman

EMILY DICKINSON is

born in 1830, the year President Andrew Jackson signs the Great Removal

act, forcibly resettling all Indians west of the Mississippi; Jackson

addresses the nation, "What good man would prefer a country covered with

forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic,

studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms, embellished with all the

improvements which art can devise or industry execute?" The Sac and Fox

tribes, over objections of chief Black Hawk, give up all their lands east

of Mississippi River ; Choctaws do the same; other tribes like Chickasaws

follow suit within a year or two. Only the Cherokees, literate farmers who

wanted citizenship, hold out. In 1832, Black Hawk leads some Sac and Fox

back across Mississippi into Illinois --they are eventually ambushed and

massacred in the Michigan Territory , and Black Hawk is turned over to

U.S. authorities by the Winnebago Indians. Major Congressional debate is

over whether or not the sale of Western lands should be restricted;

Western senators sense a plot by Eastern business interests to close the

West so that cheap labor stays in the Northeast where factories demand

low-paid workers. Joseph Smith publishes "The Book of Mormon", based on

his deciphering of golden plates he claimed to have found on an upstate

New York mountain, detailing the true church as descended through American

Indians who were apparently part of the lost tribes of Israel (an idea

quite common in early 19th-century America). The next year, 1831, Alexis

de Tocqueville arrives in the U.S. and begins his journey around the

country that would result in his massive book of observations, "Democracy

in America ," including his analysis of “the three races in America ”

(black, red, and white). Nat Turner, a Virginia slave who had visions from

God of white spirits and black spirits engaged in bloody combat, leads a

revolt with seven other slaves, killing his master and his family; with 75

insurgent slaves, he killed more than 50 whites on a two-day journey to

Jerusalem, Virginia, where he was hanged along with sixteen of his

companions (many other blacks are killed during the manhunt for Turner).

The Turner Insurrection was the stuff of nightmares for white Southerners,

who passed increasingly severe slave codes. The song "America" is sung for

the first time in Boston on July 4.

Poetry

If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me I

know that is poetry. If I feel

physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that

is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other

way?

Dickinson’s editing process often focused on word choice rather than on

experiments with form or structure. She recorded variant wordings with a “+”

footnote on her manuscript. Sometimes words with radically different

meanings are suggested as possible alternatives. [...] Because Dickinson did

not publish her poems, she did not have to choose among the different

versions of her poems, or among her variant words, to create a "finished"

poem. This lack of final authorial choices posed a major challenge to

Dickinson’s subsequent editors.

—"

Diction,"

Major Characteristics of Dickinson's Poetry,

Emily Dickinson Museum

(2009)

Poems (1891)

|

|

“Hope” is the thing with feathers -

That perches in the soul -

And sings the tune without the words -

And never stops - at all -

And sweetest - in the Gale - is heard -

And sore must be the storm -

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm -

I’ve heard it in the chillest land -

And on the strangest Sea -

Yet - never - in Extremity,

It asked a crumb - of me. |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12 |

Poems

791

God gave a Loaf to

every Bird —

But just a Crumb — to Me —

I dare not eat it — tho’ I starve —

My poignant luxury —

To own it — touch it —

Prove the feat — that made the Pellet mine —

Too happy — for my Sparrow’s chance —

For Ampler Coveting —

It might be Famine — all around —

I could not miss an Ear —

Such Plenty smiles upon my Board —

My Garner shows so fair —

I wonder how the Rich — may feel —

An Indiaman — An Earl —

I deem that I — with but a Crumb —

Am Sovereign of them all —

|

5

10

15

|

—Emily Dickinson, “God gave a Loaf to every

Bird —,” The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by Thomas

H. Johnson, Little, Brown, 1960, p. 386.

690

Victory comes late —

And is held low to freezing lips —

Too rapt with frost

To take it —

How sweet it would have tasted —

Just a Drop —

Was God so economical?

His Table’s spread too high for Us —

Unless We dine on tiptoe —

Crumbs — fit such little mouths —

Cherries — suit Robins —

The Eagle’s Gold Breakfast strangles — Them —

God keep His Oath to Sparrows —

Who of little Love — know how to starve —

|

5

10

|

—Emily Dickinson, “Victory comes late —,” The

Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by Thomas H. Johnson,

Little, Brown, 1960, p. 340.

579

I had been hungry, all

the Years —

My Noon had Come — to dine —

I trembling drew the Table near —

And touched the Curious Wine —

’Twas this on Tables I had seen —

When turning, hungry, Home —

I looked in Windows, for the Wealth

I could not hope — for Mine —

I did not know the ample Bread —

’Twas so unlike the Crumb

The Birds and I, had often shared

In Nature’s — Dining Room —

The Plenty hurt me — ’twas so new —

Myself felt ill — and odd —

As Berry — of a Mountain Bush —

Transplanted — to the Road —

Nor was I hungry — so I found

That Hunger — was a way

Of Persons outside Windows —

The Entering — takes away —

|

5

10

15

20

|

—Emily Dickinson, “I had been hungry, all

the Years —,” The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by

Thomas H. Johnson, Little, Brown, 1960, p. 283.

Letters

To T. W. Higginson

15 April

1862

Mr.

Higginson,

Are you

too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?

The mind

is so near itself—it cannot see, distinctly—and I have none to ask—

Should you

think it breathed—and had you the leisure to tell me, I should feel quick

gratitude—

If I make

the mistake—that you dared to tell me—would give me sincerer honor—toward

you—

I enclose

my name—asking you, if you please—Sir—to tell me what is true?

That you

will not betray me—it is needless to ask—since Honor is it's [sic] own

pawn—

—Emily

Dickinson, Selected Letters, edited by Thomas H. Johnson, Belknap

P, 1971, p. 171.

To T. W.

Higginson

25 April

1862

Mr.

Higginson

Your

kindness claimed earlier gratitude—but I was ill—and write today, from my

pillow.

Thank you

for the surgery—it was not so painful as I supposed. I bring you others—as

you ask—though they might not differ—

While my

thought is undressed—I can make the distinction, but when I put them in

the Gown—they look alike, and numb.

You asked

how old I was? I made no verse—but one or two—until this winter—Sir—

I had a

terror—since September—I could tell to none—and so I sing, as the Boy does

by the Burying Ground—because I am afraid—You inquire my Books—For Poets—I

have Keats—and Mr and Mrs Browning. For Prose—Mr Ruskin—Sir Thomas

Browne—and the Revelations. I went to school—but in your manner of the

phrase—had no education. When a little Girl, I had a friend, who taught me

Immortality—but venturing too near, himself—he never returned—Soon after,

my Tutor, died—and for several years, my Lexicon—was my only

companion—Then I found one more—but he was not contented I be his

scholar—so he left the Land.

You ask of

my Companions Hills—Sir—and the Sundown—and a Dog—large as myself, that my

Father bought me—They are better [end of page 172] than beings—because

they know—but do not tell—and the noise in the Pool, at Noon—excels my

Piano. I have a Brother and Sister—My Mother does not care for thought—and

Father, too busy with his Briefs—to notice what we do—He buys me many

Books—but begs me not to read them—because he fears they joggle the Mind.

They are religious—except me—and address an Eclipse, every morning—whom

they call their "Father." But I fear my story fatigues you—I would like to

learn—Could you tell me how to grow—or is it unconveyed—like Melody—or

Witchcraft?

You speak

of Mr Whitman—I never read his Book—but was told that he was disgraceful—

I read

Miss Prescott's "Circumstance," but it followed me, in the Dark—so I

avoided her—

Two

Editors of Journals came to my Father's House, this winter—and asked me

for my Mind—and when I asked them "Why," they said I was penurious—and

they, would use it for the World—

I could

not weigh myself—Myself—

My size

felt small—to me—I read your chapters in the Atlantic—and experienced

honor for you—I was sure you would not reject a confiding question—

Is

this—Sir—what you asked me to tell you?

Your

friend,

E—Dickinson.

—Emily

Dickinson, Selected Letters, edited by Thomas H. Johnson, Belknap

P, 1971, p. 172–73.

|

Study Questions

- Look up some words that

seem to have idiosyncratic meanings for Dickinson. Go to the

Hyper-Concordance to the Works of Emily

Dickinson and consider her uses of some of the

following terms. What is the difference between dictionary

definitions and Dickinson's meanings?

- bird(s)

- crumb(s)

- hope

- soul

- stop(s, -ed)

- thing

- Aside from specific words,

notice as well how Dickinson expresses ideas via groups of

imagery and categories of metaphor. Look, for instance, at

some of the following clusters of ideas and tropes. Explain

how the metaphors and imagery suit Dickinson's ideas.

- Food imagery

- Eating

- Coldness

- Quantity

- Size

- The

speaker/persona

- Time

- How is hope portrayed in

the first stanza? What qualities are stressed?

- How has the portrayal of

hope changed in the second stanza?

- How does the etymological

meaning of abashed clarify the sense of hope

depicted in this middle stanza?

- What does the poem

suggest might threaten hope? Can hope be threatened

if it "never stops — at all" (l. 4)?

- In what way does "so

many" at the end of stanza 2 set up the introduction of "I"

in stanza 3?

- How personal or

impersonal is the declaration "I've heard it in the chillest

land — / And on the strangest Sea —" (ll. 9–10)?

- What effect does "Yet"

have in the sense of personal or impersonal in the last two

lines? What turn, so to speak, does the conjunction

announce?

- What difference, if

any, is there in the sense of never in the first

stanza compared to in the last?

- How do the dashes and line

breaks shape the rhythm of the text and affect the meaning

of the poem?

- Examine the curious last

line.

- Why is the verb ask

used? Since "the thing with feathers" is hope, why

does it not give rather than ask for?

- Why is it significant

to the speaker that "the little Bird" "never" asked for a

crumb?

- What do you make of the

result of the build-up of the poem that it culminates with

"of me"? What point is being conveyed by the speaker

specifically stating that he/she personally has never been

asked for even a small bit of crumb from "hope"?

- How are we to read

this last line? Which sense does the poem suggest?

- Hope has never

visited me.

- Even in the

direst, utmost of circumstances that could endanger it,

hope has never deigned/seen fit to come find any small

resources from me.

- Hope does not

want or require any payment or nourishment for itself.

For hope to exist, there is no need to feed it or to

give it anything in return.

|

Vocabulary

fascicle

lyric

diction; denotation, connotation

ambiguity

definition; definition poem

irony

pathos

logos

form

stanza

meter; common meter

rhyme

repetition

punctuation; dash

imagery

metaphor

tone

theme

Sample

Student

Responses to Emily Dickinson's "'Hope' is the thing with feathers —"

Response

1:

Reference

| Link |

Texts

Secondary Texts

- "Guide

to Emily Dickinson's Collected Poems," Academy

of American Poets (2000)

- "'Hope' is the thing with feathers,"

Representative Poetry Online, University of Toronto

(poem text with notes)

- Domhnall Mitchell, "Cordoning

Off Dissent: Dickinson's Monologic Voices," Emily Dickinson: Monarch

of Perception (Amherst: U of Massachusetts P,

2000)

- Marjorie Perloff, "Emily

Dickinson and the Theory Canon", Electronic Poetry

Center, University of Pennsylvania

- Kamilla Denman, "Emily

Dickinson's Volcanic Punctuation," The

Emily Dickinson Journal, vol. 2, no. 1 (1993)

Textual Criticism

Resources

|

Reference

Dickinson, Emily. The

Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. Edited by Thomas H.

Johnson. Little, Brown, 1960.

Further

Reading

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily

Dickinson. Ed. Thomas H. Johnson. Cambridge: Belknap, 1958. Print.

Eberwein, Jane

Donahue, Stephanie Farrar, and Cristanne Miller, eds. Dickinson

in Her Own Time: A Biographical Chronicle of Her Life, Drawn from

Recollections, Interviews, and Memoirs by Family, Friends, and

Associates. Iowa: U of Iowa P, 2015. Print.

Grabher,

Gudrun, Roland Hagenbüchle, and Cristanne Miller, eds. The

Emily Dickinson Handbook. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 1998.

Print.

Griffith,

Clark. The Long Shadow: Emily

Dickinson's Tragic Poetry. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1964. Print.

Kirby, Joan. Emily Dickinson. New York: St.

Martin's Press, 1991. Print.

Martin,

Wendy. The Cambridge Companion to Emily

Dickinson. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2002. Print.

Martin,

Wendy. The Cambridge Introduction to

Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007. Print.

Miller,

Cristanne. Emily Dickinson: A Poet's

Grammar. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1989. Print.

Miller,

Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily

Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: U of Massachusetts

P, 2012. Print.

Mitchell,

Domhnall. Emily Dickinson: Monarch of

Perception. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 2000. Print.

Sewall,

Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson.

New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1974. Print.

Smith,

Martha Nell, and Mary Loeffelholz, eds. A

Companion to Emily Dickinson. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. Print.

Socarides,

Alexandra. Dickinson Unbound: Paper,

Process, Poetics. Oxford: OUP, 2014. Print.

Home

| Literary

Terms | English Help

Last updated August 31, 2020