Faculty of Arts,

Chulalongkorn University

"I cried at Pity – not at Pain –"

(c. 1862, 1896)

Emily

Dickinson

(December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886)

I

cried at Pity – not at Pain –

|

|

I

heard a Woman say

|

|

"Poor

Child" – and something in her voice

|

|

Convicted

me –

of me –

|

|

|

|

So

long I fainted, to myself

|

5

|

It

seemed the common way,

|

|

And

Health, and Laughter, Curious things –

|

|

To

look at, like a Toy –

|

|

|

|

| To sometimes hear "Rich people" buy |

|

| And see the Parcel rolled – |

10

|

| And carried, I supposed – to Heaven, |

|

| For children, made of Gold – |

|

| |

|

| But not to touch, or wish for, |

|

| Or think of, with a sigh – |

|

| As so and so – had been to me, |

15

|

| Had God willed differently – |

|

| |

|

| I wish I knew that Woman's name – |

|

| So when she comes this way, |

|

| To hold my life, and hold my ears |

|

| For fear I hear her say |

20 |

| |

|

| She's "sorry I am dead" – again – |

|

| Just when the Grave and I – |

|

| Have sobbed ourselves almost to sleep, |

|

| Our only Lullaby – |

|

Notes

1 cried:

- cry (Emily

Dickinson Lexicon)

cry (cried), v. [Fr. < L. quirītāre,

raise a plaintive cry, wail, scream, bewail, lament; originally, to

implore the aid of the Quirītes,

or Roman citizens.] (webplay: child, ears, giveth, joy, lives, lost,

prayed, prayer, shake, voice, woman's).

A. Say; exclaim; call out; utter

in a loud voice.

B. Sob; weep; lament; shed

tears.

1

Pity:

- pity (Emily

Dickinson Lexicon)

pity, n. [ME < OFr < L. pietās,

dutifulness, piety.] (webplay: children, fear, painful, poor).

A. Empathy; sensitivity to

another's affliction; perception of suffering; awareness of pain; desire

to relieve another's misery. (496/364, 588/394)

B. Condescending compassion;

patronizing sympathy. (229/289, 496/364)

C. Unfortunate circumstance;

regrettable fact; lamentable but unchangeable problem.

D. [Fig.] mourning; grief;

sorrow; tears of those bereaved.

1

Pain:

- pain (Emily

Dickinson Lexicon)

pain (-'s), n. [ME < OFr peine <

L. pœna penalty, punishment.]

(webplay: animal, bodies, bowed, childbirth, death, difficult,

displeasure, expect, fear, fly, friends, future, gain, grief, heart,

inflicted, limb, lose, mind, parts, past, pressure, presume, prospect,

service, sorrow, suffer, surgery, taking pains to rise, tired, trouble,

uneasy, work).

A. Trial; mental difficulty;

emotional suffering; spiritual agony.

B. Hurt; discomfort; physical

suffering; bodily affliction.

C. Work; labor; toil; exertion;

effort.

D. Grief; misery; sorrow; [fig.]

mortality; life on earth; human experience.

E. Offense; insult; pang of

regret or sorrow.

F. Ache; heartbreak; [fig.]

vein.

3

Poor:

- poor (Emily

Dickinson Lexicon)

poor (-er, -est), adj. [ME < OFr < L. pauper,

poor.] (webplay: comfortable, composition, day, ground, grows, health,

heart, land, life, little, night, people, pitiable, pretty, rich, small,

spirit, sufficient, tenderness, thing, unhappy, wealth, wholly, without,

woman, words).

A. Bereaved; deprived of a loved

one; dispossessed of the companionship of a close friend.

B. Pitiable; unfortunate;

pathetic; hapless; wretched.

C. Lowly; indigent; needy;

[fig.] vulnerable; subject to loss.

D. Sad; lost; forlorn; lonely.

E. Inferior; less in status;

lower in prestige; [fig.] mortal; human; less glorious.

F. Destitute; needy; penniless;

without possession; lacking personal property; [fig.] excluded; not

included; left out.

G. Thrifty; frugal; sparing;

stinting; scant; sparse; economical; careful.

H. Obscure; unknown; unsung;

undervalued; nameless; anonymous; not noticed.

I. Irrelevant; inferior; paltry;

inadequate; deficient; insufficient; unsatisfactory; less than ideal.

3

Child:

- child (Emily

Dickinson Lexicon)

child (-ren, -ren's, -'s), n. [OE cild

< root kilth-,

whence also Goth. kilthei,

womb, inkilthô, pregnant

woman.] (webplay: advanced, age, bearing, blow, cast, coldness, country,

fear, first, God, grace, humble, ignorant, judgment, mere, morals,

principles, race, remote, son, speak, strictness, strong, years, young).

A. Minor; little one; [fig.]

uninitiated; not yet confirmed; [metaphor] one of the least in the

Kingdom of God (see Matthew 18:2-6; 25:40).

B. Young person of either sex

below the age of puberty.

C. One weak in knowledge; a

person of immature experience or judgment.

D. Descendants; offspring;

posterity; [fig.] spiritual offspring of God.

E. Innocent; [fig.] saint;

angel; celestial being; chosen one; pure in heart people (see Matt

18:3).

F. Phrase. “the Chosen Child”:

Jesus; the Messiah; the Christ; the anointed Son of God;

[generalization] the saint; the disciple; the follower of the Lord.

4

Convicted:

- convict (Emily

Dickinson Lexicon)

convict (-ed, -s), v. [L. convict-,

stem of convinc-ere; see

convince, v.] (webplay: convince, heard, prove, show).

Prove guilty; convince of error; impress with a realization of

wrongdoing.

Cf. convinced in manuscript

- convince (Emily

Dickinson Lexicon)

convince (-d), v. [L. convinc-ere,

overcome, conquer, convict, demonstrate.] (webplay: convict, God's,

prove).

Persuade; convert; cause to accept; induce to acknowledge.

5

fainted:

- faint (Emily

Dickinson Lexicon)

faint (-ed, -ing, -s), v. [Fr. faner,

to fade, wither, decay.] (webplay: day, distillation, fail, hearing,

heart, house, lady, thirst, voice).

A. Lose heart, courage, or

spirit; (see Revelation 2:3).

B. Swoon; lose strength and

color; (see Amos 8:13).

C. Adore; worship; fall on knees

to exalt; (see Psalms 119:81).

6

common:

- common (Emily

Dickinson Lexicon)

common (-er, -est), adj. [early ME co(m)mun

< early L. munis, obliging,

ready to be of service.] (webplay: bud, children, church, confirmed,

customs, earth, estate, estimation, equally, excellence, flowers,

habits, land, life, lower, man, many, mean, owner, privileges, process,

rank, records, right, superior, tenants, time, use, woman).

A. Usual; ordinary; like any

other.

B. Familiar; less distinguished;

of lower prestige; undistinguished by superior characteristics.

C. Communal; general; belonging

equally to all.

8

Toy:

- toy (Emily

Dickinson Lexicon)

toy (-s), n. [etymology unknown.] (webplay: children, gold, stay).

Child's plaything; thing for amusement with no real value.

19

hold:

- hold (Emily

Dickinson Lexicon)

hold (-ing, -s, held), v. [OE haldan

< Germanic.] (webplay: anchor, arms, basket, bearing, blow,

carry, child, contain, curtain, debate, distance, dollar, endure,

escape, estate, exhibit, fail, fast, fix, fool, frost, grace, hand,

head, horse, interrupted, judge, keep, last, laughter, lifting, limit,

measure, nature, night, offer, orange, peace, people, possession,

practice, raining, reach, running, solemnize, stand, still, stop, take,

teach, think, thunder, title, tongue, true, up, water, within). Bind;

connect;

A. Retain; contain; prevent;

restrain; confine within.

B. Bear in the hand; maintain in

one's grasp.

C. Bind; tie; secure; fasten;

connect; fix; keep; maintain.

D. Stick together; retain

cohesion; maintain position; remain immovable; stay in place; keep from

separation; refrain from dropping.

E. Think; regard; consider;

believe; maintain an opinion.

F. Contain; bear a certain

amount.

G. Own; retain.

H. Mold; shape.

I. Phrase. “hold … breath”: stay

still; remain motionless due to profound awe.

J. Phrase. “hold up”: sustain;

support.

What

was the United States like that Whitman and Dickinson were born into?

Source: Ed

Folsom, Selected American Authors: Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman

EMILY DICKINSON is

born in 1830, the year President Andrew Jackson signs the Great Removal

act, forcibly resettling all Indians west of the Mississippi; Jackson

addresses the nation, "What good man would prefer a country covered with

forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic,

studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms, embellished with all the

improvements which art can devise or industry execute?" The Sac and Fox

tribes, over objections of chief Black Hawk, give up all their lands east

of Mississippi River ; Choctaws do the same; other tribes like Chickasaws

follow suit within a year or two. Only the Cherokees, literate farmers who

wanted citizenship, hold out. In 1832, Black Hawk leads some Sac and Fox

back across Mississippi into Illinois --they are eventually ambushed and

massacred in the Michigan Territory , and Black Hawk is turned over to

U.S. authorities by the Winnebago Indians. Major Congressional debate is

over whether or not the sale of Western lands should be restricted;

Western senators sense a plot by Eastern business interests to close the

West so that cheap labor stays in the Northeast where factories demand

low-paid workers. Joseph Smith publishes "The Book of Mormon", based on

his deciphering of golden plates he claimed to have found on an upstate

New York mountain, detailing the true church as descended through American

Indians who were apparently part of the lost tribes of Israel (an idea

quite common in early 19th-century America). The next year, 1831, Alexis

de Tocqueville arrives in the U.S. and begins his journey around the

country that would result in his massive book of observations, "Democracy

in America ," including his analysis of “the three races in America ”

(black, red, and white). Nat Turner, a Virginia slave who had visions from

God of white spirits and black spirits engaged in bloody combat, leads a

revolt with seven other slaves, killing his master and his family; with 75

insurgent slaves, he killed more than 50 whites on a two-day journey to

Jerusalem, Virginia, where he was hanged along with sixteen of his

companions (many other blacks are killed during the manhunt for Turner).

The Turner Insurrection was the stuff of nightmares for white Southerners,

who passed increasingly severe slave codes. The song "America" is sung for

the first time in Boston on July 4.

Poetry

If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me I

know that is poetry. If I feel

physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that

is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other

way?

[quoting Austin] It is a little remarkable that two girls—of the Genius of

Helen Hunt and Emily Dickinson should have been within three or four years

of each other in the same quiet New England village the one the daughter of

a minister and professor in the College—the other daughter of a lawyer and

Treasurer of the College—both attracting general attention in their

childhood the one more by her wild romping rebellious Spirit and ways—the

other by her intellectual brilliancy—the one as she grew up meeting the

world fearlessly—and triumphantly—adding increasing fame with every

year—moving through the country like a Queen—the other, after 18 or 20,

gradually withdrawing herself from society till she saw very few

except members of her own family—and was known only through memory or

tradition—and her letters to those who especially interested her. In her

school days—at the primary—at [word illegible] Amherst Academy and at South

Hadley—she was not of the best scholars—but the brightest of any social

group. Her compositions were unlike anything ever heard—and always produced

a sensation—both with the scholars and Teachers—her imagination sparkled—and

she gave it free rein. She was full of courage—but always had a peculiar

personal sensitiveness. She saw things directly and just as they were. She

abhorred sham and cheapness. As she saw more and more of society—in Bos-

[end of page 222] ton where she visited often—in Washington where she spent

some time with her father when he was a member of Congress—and in other

places [The following is crossed out:]

she could not resist the feeling that it was [terribly] painfully hollow. It

was to her so thin and unsatisfying in the face of the Great realities of

Life although no one surpassed her in wit or brilliancy. [The

text resumes:] notwithstanding the fact that she was everywhere

sought for her brightness—originality & wit—

Dickinson’s editing process often focused on word choice rather than on

experiments with form or structure. She recorded variant wordings with a “+”

footnote on her manuscript. Sometimes words with radically different

meanings are suggested as possible alternatives. [...] Because Dickinson did

not publish her poems, she did not have to choose among the different

versions of her poems, or among her variant words, to create a "finished"

poem. This lack of final authorial choices posed a major challenge to

Dickinson’s subsequent editors.

—"

Diction,"

Major Characteristics of Dickinson's Poetry, Emily Dickinson Museum (2009)

There is enough here to wring pity from the stoniest heart—"'Poor Child,'"

the want of "Health, and Laughter," no presents, the sobbing "Lullaby." But

the poem is not an appeal for pity; it is a warning against it, particularly

here the kind of sentimental, uninformed pity (the "Woman" is clearly an

outsider) that brings out the worst in the one pitied. Again she uses

childhood as a metaphor for conveying an attitude toward a kind of pain that

may have nothing to do with childhood—frustration of any sort, the

experience of being excluded, or even, as has been suggested, frustration as

poet. Indeed, the poem is more about pity than [end of page 329] about pain.

Pain can be endured, she says; but she would "hold her ears" against the

kind of pity that leads only to the debasement of self-pity.

—Richard B. Sewall, "

Childhood,"

The Life of Emily Dickinson, vol.

2 (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2003)

Emily Dickinson's 'I cried at Pity – not at Pain" might almost have

been—were there any evidence that Dickinson had any acquaintance with her

exact contemporary—a complex, polysemous and mildly contemptuous riposte to

the 'very sweet' comfort Christina's persona might appear to draw from pity

and the survival of a sexual warmth she never inspired or shared [...]

Dickinson's infant persona, unaware of the meaning of vivisepulture, though

seemingly enduring it, has all the longings of a living child: after a life

in which health and happiness were as curiously rare as precious toys

wrapped and consigned to exclusive heavenly children as good as (or

incorruptible as) gold. She evokes pity even while excoriating it, detesting

what has singled her out, convicted her of her unfortunate self. She no more

wants her hand held than her life to be held as a text of compassionate

sorrow, she wants to stop up 'the access and the passage to' repulsive

compunction, seeking the only solace of the sentient corpse—sleep. But

'Sleep', of course, for both the living and the dead, 'is the station

grand', the Grand Central for all imaginative journeyings.

page

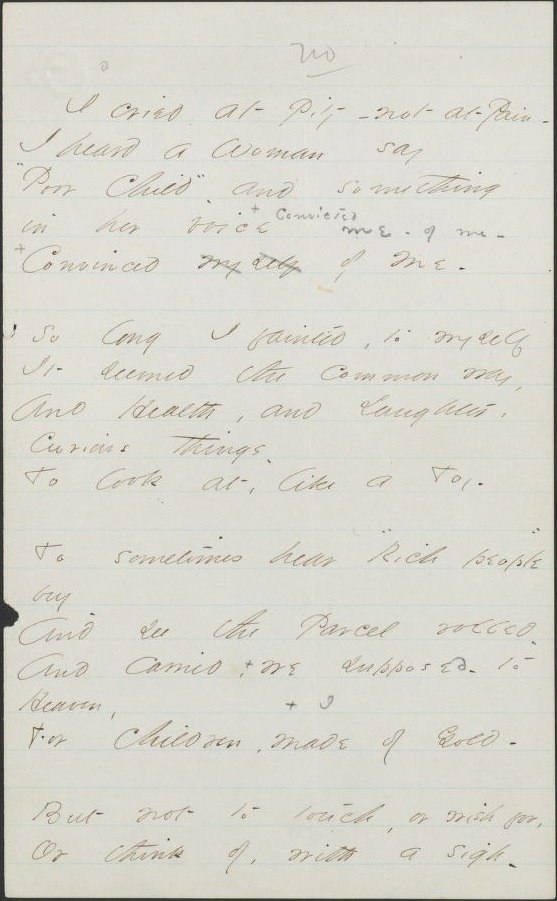

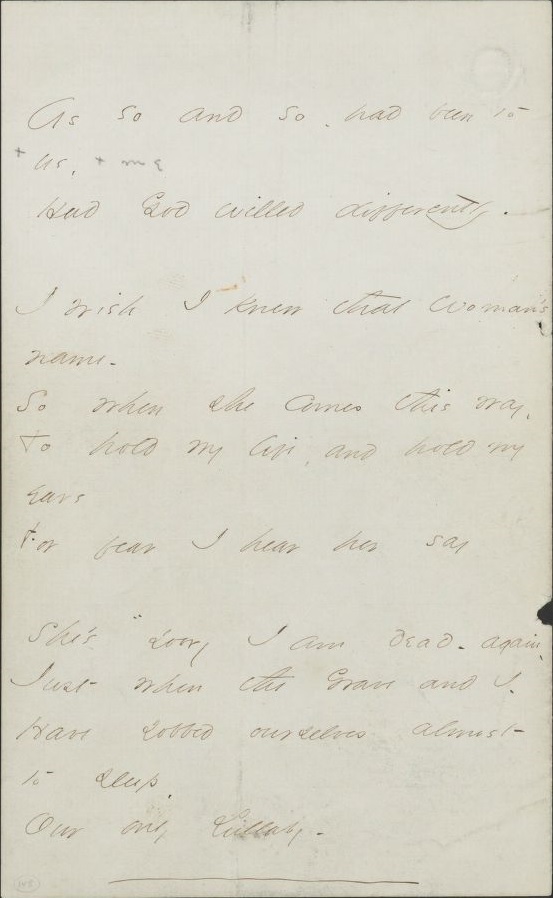

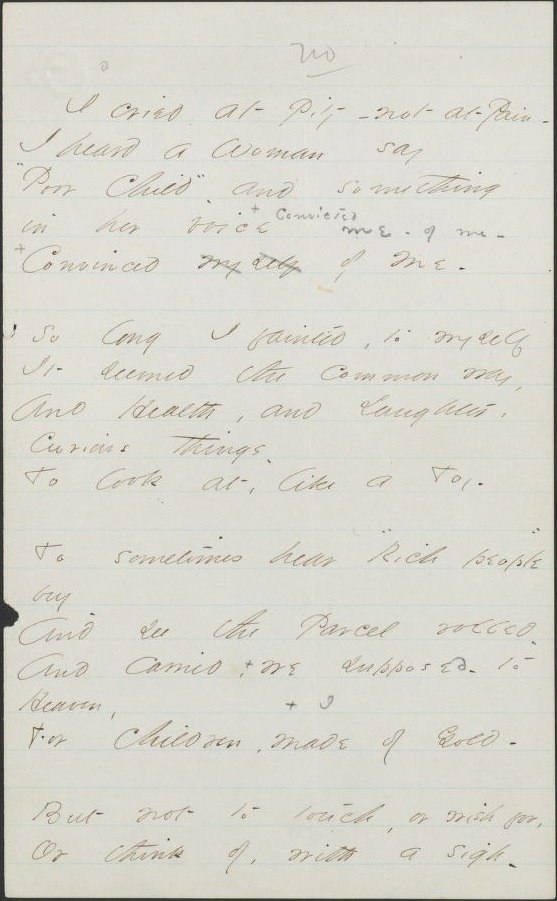

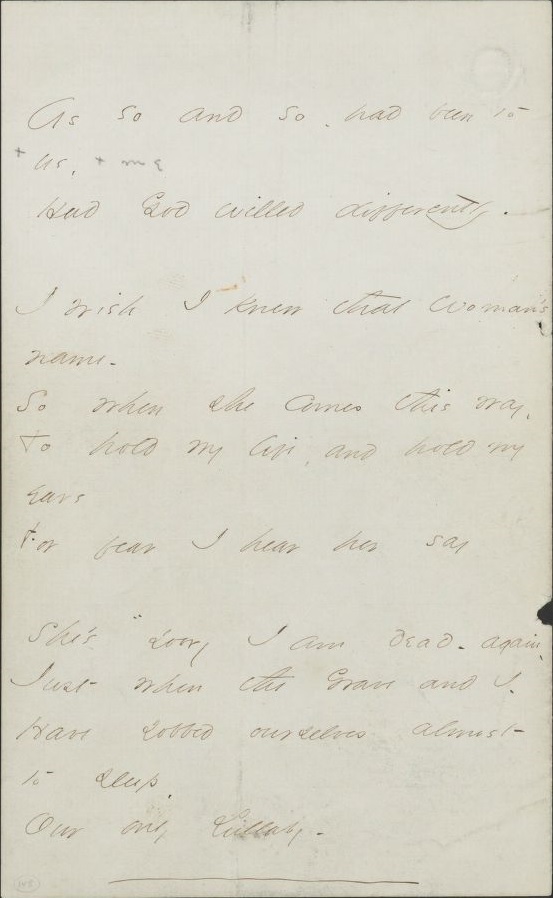

148, Poems: Packet XXVII (c.

1862)

Fascicle 19, 148c, Houghton Library, Harvard College

Fascicle 19, 148c, Houghton Library, Harvard College |

I cried at

Pity – not at Pain –

I heard a

Woman say

"Poor

Child" and something

in her

voice + Convicted me – of me –

+

Convinced my

self of Me –

So long I

fainted, to myself

It seemed

the Common way,

And

Health, and Laughter,

Curious things –

To look

at, like a toy –

To sometimes hear "Rich people"

buy

And see

the Parcel rolled –

And

Carried, + we supposed – to

Heaven,

+ I

For

Children, made of Gold –

But not to

touch, or wish for,

Or think

of, with a sigh –

As so and

so – had been to

+ us, + me

Had God

willed differently –

I wish I

knew that Woman's

name –

So when

she Comes this way,

To hold my

life, and hold my

ears

For fear I

hear her say

She's

"sorry I am dead – again –

Just when

the Grave and I –

Have

sobbed ourselves almost

to sleep –

Our only

Lullaby –

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32 |

Your

Riches – taught me – Poverty.

|

|

Myself

– a Millionaire

|

|

In

little Wealths, as Girls could boast

|

|

Till

broad as Buenos Ayre –

|

|

|

|

You drifted your Dominions –

|

5

|

A

Different Peru –

|

|

And

I esteemed All Poverty

|

|

For

Life's Estate with you –

|

|

|

|

| Of Mines, I little know – myself – |

|

| But just the names, of Gems – |

10

|

| The Colors of the Commonest – |

|

| And scarce of Diadems – |

|

| |

|

| So much, that did I meet the Queen – |

|

| Her Glory I should know – |

|

| But this, must be a different Wealth – |

15

|

| To miss it – beggars so – |

|

| |

|

| I'm sure 'tis India – all Day – |

|

| To those who look on You – |

|

| Without a stint – without a blame, |

|

| Might I – but be the Jew – |

20 |

| |

|

| I'm sure it is Golconda – |

|

| Beyond my power to deem – |

|

| To have a smile for Mine – each Day, |

|

| How better, than a Gem! |

|

| |

|

| At least, it solaces to know |

25 |

| That there exists – a Gold – |

|

| Altho' I prove it, just in time |

|

| Its distance – to behold – |

|

| |

|

| Its far – far Treasure to surmise – |

|

| And estimate the Pearl – |

30 |

| That slipped my simple fingers through – |

|

| While just a Girl at School. |

|

—Emily

Dickinson, The Complete Poems of Emily

Dickinson, ed. Thomas H. Johnson (Boston: Little, Brown, 1960):

141.

When Emily Dickinson sent this poem over the hedge to her sister-in-law,

Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson, in 1862, she prefaced it with the

salutation, "Dear Sue," as if to underline the character of the poem as a

personal note. She followed it with the simple words: "Dear Sue—You see I

remember, Emily." What Emily was "remembering"—and saying good-bye to in

this poem was their girlhood romance, which, by 1862, had existed only in

memory for quite some time.

I

play at Riches – to appease

|

|

The

Clamoring for Gold –

|

|

It

kept me from a Thief, I think,

|

|

For

often, overbold

|

|

|

|

With

Want, and Opportunity –

|

5

|

I

could have done a Sin

|

|

And

been Myself that easy Thing

|

|

An

independent Man –

|

|

|

|

| But often as my lot displays |

|

| Too hungry to be borne |

10

|

| I deem Myself what I would be – |

|

| And novel Comforting |

|

| |

|

| My Poverty and I derive – |

|

| We question if the Man – |

|

| Who own – Esteem the Opulence – |

15

|

| As We – Who never Can – |

|

| |

|

| Should ever these exploring Hands |

|

| Chance Sovereign on a Mine – |

|

| Or in the long – uneven term |

|

| To win, become their turn – |

20 |

| |

|

| How fitter they will be – for Want – |

|

| Enlightening so well – |

|

| I know not which, Desire, or Grant – |

|

| Be wholly beautiful – |

|

—Emily

Dickinson, The Complete Poems of Emily

Dickinson, ed. Thomas H. Johnson (Boston: Little, Brown, 1960):

391.

This text stretches across a

multitude of arenas, with gender both a fulcrum and a prism. The speaker

of the poem first seems, as recurs in Dickinson, to be male, exactly

because of its economic reference. This "I" tries to constitute himself

through what was just emerging at the time of writing as an increasingly

dominant American self-definition: "Riches." This becomes explicit in the

lines "And been Myself that easy Thing / An independent Man –." But such

cultural definition of the self in economic terms is what the poem goes on

to examine and complicate, with peculiar gender shifts along the way. "The

Clamoring for Gold" casts "Riches" as something restless and desperate. It

is, as the poem pursues, a form of lack, of "Want," tempting to "a Thief"

or to a kind of negative "Opportunity," or even, as the poem continues, a

temptation to "Sin." Perhaps this is a reference to religious suspicions

of material wealth as betraying inner spirituality, even as, in traditions

of Puritan America famously explicated by Max Weber, wealth is also

spirit's outward sign. Or perhaps "Sin" registers Dickinson's own

suspicion against her culture's increasing turn to materialist measures of

selfhood. "Riches" as the American dream of independent Manhood is here

almost dismissed as too "easy," in contrast to genuine achievement, and

threatens reduction to a "Thing."

In a

manuscript variant, however, instead of "easy" Dickinson writes "distant."

To be an "independent Man" is indeed distant from her because she is a

woman. Her approach to "Riches" remains mere "play," in part because her

"lot" is one not of overabundance but of dearth, a "Poverty" "Too hungry

to be borne." "Riches" is denied her, not least as a female who, at the

time of writing, had at best very limited property rights. Yet there is

also "novel Comforting" derived in her "Poverty." Here Dickinson enters

into her persistent practice of weighing, and recasting, gain against

loss. "Riches" seems obvious gain. Yet the "Man / Who own" does not in the

end sufficiently "Esteem the Opulence" he seeks. As to the speaker, if he

or she "never Can" attain such opulence, then he or she also more fully

takes its measure, not only because unable to achieve it, but also through

questioning its value.

—Shira

Wolosky, "Gendered

Poetics," Emily Dickinson in

Context, ed. Eliza Richards (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2013)

Paraphrases

I cried

at Pity – not at Pain –

I heard a Woman say

"Poor Child" – and something in her voice

Convicted me – of me –

So long I fainted, to myself

It seemed the common way,

And Health, and Laughter, Curious things –

To look at, like a Toy –

To sometimes hear "Rich people" buy

And see the Parcel rolled –

And carried, I supposed – to Heaven,

For children, made of Gold –

But not to touch, or wish for,

Or think of, with a sigh –

As so and so – had been to me,

Had God willed differently –

I wish I knew that Woman's name –

So when she comes this way,

To hold my life, and hold my ears

For fear I hear her say

She's "sorry I am dead" – again –

Just when the Grave and I –

Have sobbed ourselves almost to sleep,

Our only Lullaby – |

I cried at pity –

not at pain – I heard a woman say "poor child" – and something in

her voice convicted me – of me –

So long I fainted, to myself it seemed the common way, and health,

and laughter, curious things – to look at, like a toy –

To sometimes hear "rich people" buy and see the Parcel rolled –

and carried, I supposed – to heaven, for children, made of gold –

but not to touch, or wish for, or think of, with a sigh – as so

and so – had been to me, had God willed differently – I wish I

knew that woman's name – so when she comes this way, to hold my

life, and hold my ears for fear I hear her say she's "sorry I am

dead" – again – just when the grave and I – have sobbed ourselves

almost to sleep, our only lullaby –

|

|

|

| I cried because of

pity, not because of pain. I heard a woman say "poor child" and

something in her voice made me guilty of being myself. I was weak

for so long that it seemed normal to me, and health and laughter

seemed strange things to witness, like an amusing toy. To

sometimes hear "rich people" buying a package and see the package

wrapped and taken (I assumed) to heaven for children who are made

of gold but not the kind of gold to touch, wish for, or think of

with a sigh as someone had done so to me, had God willed

differently. I wish I knew that woman's name so that when she

comes to where I am, to hold my life, and hold my ears because she

is afraid I might hear her say again that she's "sorry I am dead"

just when the grave and I have cried ourselves almost to sleep.

This crying is our only lullaby. |

|

|

| I cried from pity,

not from pain. I heard a woman say "poor child" and something in

her voice made it wrong for me to be me. I was weak for so long

that I thought it was ordinary to be so, and it was strange to see

health and laughter; it was like looking at an amusing trivial

plaything. To sometimes hear "rich people" buying a package and

see the package wrapped and taken (I assumed) to heaven for

children who are made of gold but not the kind of gold to touch,

wish for, or think of with a sigh the way someone had done to me,

had God done things differently. I wish I knew that woman's name

so that when she comes to the place where I am, to hold my life,

and to hold my ears because she is afraid that I might hear her

say again that she's "sorry I am dead" just when the grave and I

have cried ourselves almost to sleep. This crying is our only

lullaby. |

|

Study Questions

- What is the difference between dictionary definitions and

Dickinson's meanings?

- In the paraphrases above, when the dashes are taken out and

the line breaks removed, how do the lines read differently and

to what extent does this change the meaning of the lines?

- Which meanings of hold in

the Emily

Dickinson Lexicon can apply to this poem?

|

Vocabulary

fascicle

lyric

diction; denotation, connotation

figurative meaning

ambiguity

circumlocution

definition; definition poem

riddle; riddle poem

irony

pathos

logos

form

stanza

meter; common meter

rhyme

repetition

punctuation; dash

imagery

symbolism, symbols, symbolic

tone

theme

Sample

Student

Responses to Emily Dickinson's "I cried at Pity – not at Pain –"

Response

1:

Reference

| Link |

Texts

Secondary Texts

Textual Criticism

Resources

|

Emily

Dickinson

|

- "Emily

Dickinson," The

Heath Anthology of American Literature, 5th

ed., ed. Paul Lauter (brief bio)

- Emily

Dickinson (brief bio)

- Emily

Dickinson (longer biography)

- Karen Ford, ed., "Emily

Dickinson (1830–1886)," Modern

American Poetry, University of Illinois at

Urbana-Champaign

- Emily

Dickinson Museum (biography,

schooling,

faith,

health,

death,

family

and friends, letters,

poetry

characteristics)

|

Reference

Dickinson, Emily. The

Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. Ed. Thomas H. Johnson.

Boston: Little, Brown, 1960. Print.

Further

Reading

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily

Dickinson. Ed. Thomas H. Johnson. Cambridge: Belknap, 1958. Print.

Eberwein, Jane

Donahue, Stephanie Farrar, and Cristanne Miller, eds. Dickinson

in Her Own Time: A Biographical Chronicle of Her Life, Drawn from

Recollections, Interviews, and Memoirs by Family, Friends, and

Associates. Iowa: U of Iowa P, 2015. Print.

Grabher,

Gudrun, Roland Hagenbüchle, and Cristanne Miller, eds. The

Emily Dickinson Handbook. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 1998.

Print.

Griffith,

Clark. The Long Shadow: Emily

Dickinson's Tragic Poetry. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1964. Print.

Kirby, Joan. Emily Dickinson. New York: St.

Martin's Press, 1991. Print.

Martin,

Wendy. The Cambridge Companion to Emily

Dickinson. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2002. Print.

Martin,

Wendy. The Cambridge Introduction to

Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007. Print.

Miller,

Cristanne. Emily Dickinson: A Poet's

Grammar. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1989. Print.

Miller,

Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily

Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: U of Massachusetts

P, 2012. Print.

Mitchell,

Domhnall. Emily Dickinson: Monarch of

Perception. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 2000. Print.

Sewall,

Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson.

New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1974. Print.

Smith,

Martha Nell, and Mary Loeffelholz, eds. A

Companion to Emily Dickinson. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. Print.

Socarides,

Alexandra. Dickinson Unbound: Paper,

Process, Poetics. Oxford: OUP, 2014. Print.

Home | Reading and Analysis for the Study of

English Literature | Literary Terms | English Help

Last updated April 24, 2016