Faculty of Arts,

Chulalongkorn University

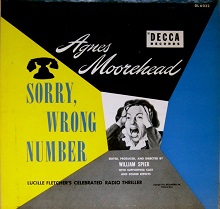

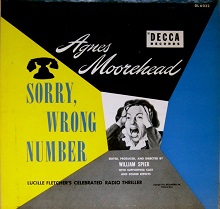

Sorry, Wrong Number

(1948)

Lucille

Fletcher

(March 28, 1912 – August 31, 2000)

Notes

Sorry, Wrong Number was first written and performed as a radio play,

broadcast on May 25, 1943.

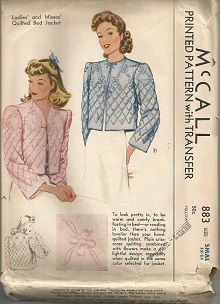

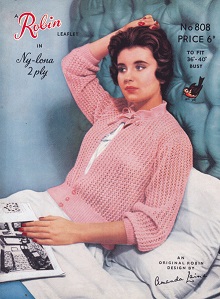

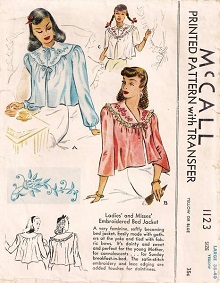

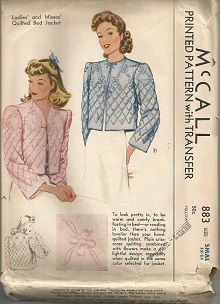

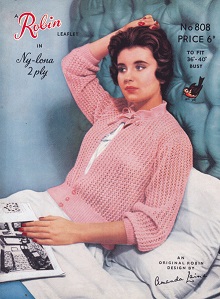

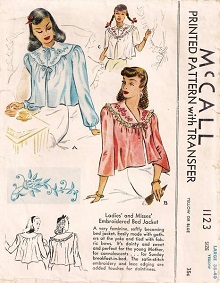

148 bed-jacket:

Quilted bed jacket

Knit bed jacket

Embroidered bed jacket

Barbara Stanwyck as Mrs. Stevenson in Sorry, Wrong Number,

directed by Anatole Litvak, 1948.

|

- bed jacket (Merriam-Webster)

a short lightweight

jacket worn over a nightgown often when sitting up in bed

- "Bed Jacket," The Dictionary of

Fashion History, by Valerie Cumming (2010)

A short jacket worn in bed; of various fabrics and often, in

the early to mid-20th century, home-made and/or hand-knitted.

- Hollis Jenkens, "Bed Jacket," Vintage Fashion Guild

(2010).

A bed jacket is a short, below bust or waist length jacket

specifically intended be worn in bed while sitting up. Worn

over the nightgown, the bed jacket can be found in a wide

variety of fabrics and treatments. It is most likely derived

from 19th combing jackets, and was popular into the early

1960s.

- Debbie Sessions, "1940s Sleepwear: Nightgowns, Pajamas, Robes,

Bed Jackets," The Vintage Dancer (2015)

Bed jackets were a nighttime staple in the ’40s. Bed jackets

had two uses. One use was a short covering to wear over

sleepwear while taking care of her nightly beauty routine. The

other use was a light layer of warmth for cool evenings and

mornings. Many movies portray women sitting up in bed, reading

with a bed jacket on.

1940s Knit sweater-like bed jackets called "cuddlies." Popular

colors were white, pale pink, peach and light blue with white

trim.

The style of the time was a cropped jacket with elbow-length

or slightly shorter than wrist length sleeves. It was about

waist-length or a little longer. The jacket was cut straight

and was loose fitting in both the jacket and sleeves. Trim is

abundant, usually in a contrasting color. These jackets could

tie around the neck with a ribbon, close with one button in

the center, or button all the way down. They could be thin

cotton or rayon satin, and were often quilted in winter

weights. Some were also knitted and sweater-like, called

“cuddlies.” Popular colors were white, pale pink, peach and

light blue with white trim.

- "Bed-Jacket," Illustrated

Encyclopedia of World Costume, by Doreen Yarwood (1978)

A modern garment designed as a pretty jacket to wear over a

nightdress for warmth and elegance while in bed.

|

148 switchboard:

153 redtape:

- red tape (Merriam-Webster)

official routine or procedure marked by excessive complexity which

results in delay or inaction

Origin and Etymology of red tape

from the red tape formerly used to bind legal documents in England

Background

Miss Fletcher once

described ''Sorry, Wrong Number'' as an experiment in radio sound effects.

''I grew up in an era when the radio was a wonderful medium for the

imagination,'' she said. ''You could get any effect you wanted with

sounds.''

Her daughter Dorothy Herrmann said Miss Fletcher got the idea for the

drama after an obnoxious well-dressed woman refused to permit her to go

ahead on a supermarket checkout line on Manhattan's East Side when Miss

Fletcher was buying some milk or cereal for one of her children, who was

sick.

''No, you cannot,'' the woman said. ''How dare you?''

The drama, Ms. Herrmann said, was Miss Fletcher's act of revenge.

[...]

In an interview

with The Washington Post, Miss Fletcher once said: ''Writing

suspense stories is like working on a puzzle. You bury the secret, lead

the reader down the path, put in false leads and throughout the story

remain completely logical. Each word must have meaning and be written in a

fine literary style. Mysteries are a challenge, a double task for the

writer, for the reader is aching to solve the puzzle before you do.''

—Lawrence

van Gelder, "Lucille Fletcher, 88, Author of 'Sorry, Wrong Number,'"

The New York Times, 6 Sep. 2000.

Kurt Andersen:

Suspense was an anthology show that ran on CBS radio from 1942 until the

very end of the golden age of radio in the fall of 1962. I think the

narrator of Suspense very early on in the show’s run said it was about

presenting a precarious situation and then withholding the solution

until the last possible moment.

[...]

Kurt Andersen: Lucille

Fletcher who wrote the script wrote Mrs. Stevenson as, frankly, not a

terribly likeable woman.

Dorothy Herrmann: My mother came from a working class

family in Brooklyn and she won a scholarship to Vassar College. And as a

poor scholarship student she felt that these very rich girls who came to

school in their limousines—she felt that they snubbed her. And, to make

matters worse, she had a boyfriend who was an upperclass young man who was

studying at Dartmouth. And he had a mother who was very much like Mrs.

Stevenson. And she looked down on my mother. And this made my mother very

miserable. So I think that she was taking a revenge on a lot of people in

her radio play.

Dorothy Herrmann: My mother came from a working class

family in Brooklyn and she won a scholarship to Vassar College. And as a

poor scholarship student she felt that these very rich girls who came to

school in their limousines—she felt that they snubbed her. And, to make

matters worse, she had a boyfriend who was an upperclass young man who was

studying at Dartmouth. And he had a mother who was very much like Mrs.

Stevenson. And she looked down on my mother. And this made my mother very

miserable. So I think that she was taking a revenge on a lot of people in

her radio play.

[...]

Kurt Andersen: When

she’s [Mrs. Stevenson's] attacked in her bedroom Agnes Moorehead

screams. And she worked it out so that her scream would be the exact

pitch of the whistle of the train that was going by her home. I think it

was one of the first times that someone had had the audacity to go on

radio, this national network, and present a story in which the killers

get away.

Dorothy Herrmann: I

think my mother took delight in the end of Mrs. Stevenson, that she’s

trapped by her own invalidism and her own neuroticism, and also the fact

that nobody will believe her.

—Kurt

Andersen, "Sorry,

Wrong Number," Studio 360, WNYC,

26 Nov. 2015.

A clerk-typist for

CBS radio in New York city, Lucille Fletcher prepared the manuscripts of

other playwrights and soon realized that she could probably do better. Her

first story was about a man who drove across the country while being

stalked by the same hitchhiker everywhere. [...] The success of The

Hitch-Hiker raised Fletcher's status at CBS from clerk-typist to

scriptwriter. she didn't waste any time. Her next radio play, Sorry,

Wrong Number, premiered in 1943 on Suspense and quickly

became one of the most legendary radio plays of all time, second perhaps

only to The War of the Worlds.

[...]

Marooned in her

bedroom, Mrs. Stevenson attempts a kind of remote control over her

narrowly confined world by telephone. Although Mrs. Stevenson reaches out

to others, the unfriendly phone system refuses to provide her with a

dialogic partner. She is trapped in a monologic system that not only

isolates her but persecutes her for speaking.

[...]

Agnes Moorehead was

widely praised for her performance in the story. [...] Mrs. Stevenson is

not only neurotic and paranoid but also irritable, sarcastic, ill-natured,

and mean. [...] She is an acoustic spectacle, an eruption of female

hysteria, and Moorehead's ability to capture the unacceptable side of the

female speaking subject seized the imaginations of listeners everywhere

and spurred many to phone CBS requesting additional performances of the

radio play.

Discursive

Deviancy

What was it about

Moorehead's voice that aroused such fascination? The suggestion that a

woman cannot be safe even in her own home was certainly relevant and

compelling; however, as Allison McCracken suggests, Mrs. Stevenson might

be the victim of the story but she was also its "monster." [...] Together,

Lucille Fletcher and Agnes Moorehead test the very limits of deviant

female subjectivity with their hyperbolizing of Mrs. Stevenson as the

madwoman in the attic, creating in the guise of a thirty-minute radio play

the anatomy of a screaming woman.

[...]

Sorry, Wrong

Number was written specifically for Moorehead because Fletcher

wanted an ornery voice for Mrs. Stevenson. Moorehead delivered. [...]

[...] Not only does

she violate the convention of "The Good Wife" as someone who should speak

in a low, soft, soothing, and pleasant voice, but Mrs. Stevenson also

complicates the position of listeners by implicating them in her own

predicament. As Suspense's narrator explains during the program's

introduction, Sorry, Wrong Number is a story of a woman who

"overheard a conversation with death." Mrs. Stevenson herself, in other

words, is a listener. She is engrossed by a mystery, a murder plot, much

the same way the radio audience is tuned in to CBS's thriller. [...]

[...]

[...] The killers

can't hear her, and the phone operator and the police ignore her. Her

husband, by proxy, will apparently silence her. The audience, however,

hears every word. Mrs. Stevenson is up against an information system that

will not acknowledge her voice, as if she spoke the wrong language (which,

of course, she does). Her distress is not only a result of patriarchy but

also of telephony's refusal to admit her into its mediatory network. This

is not what Ma Bell (“The Voice with a Smile”) promised. Period ads

pitched the phone operator as “alert” and “courteous.” “They’re nice

people to do business with,” pledged a 1939 ad for Bell Telephone System.

The phone operator with a “smiling voice” was an invitation to talk,

someone expected to “exercise a soothing and calming effect” on callers, a

woman on hand to help reduce the isolation of other women. [...]

[...]

By grounding the

story in a succession of telephone exchanges experienced by an isolated

woman confined to her bedroom, Fletcher created a narrative that seems

ideally suited to the uniqueness of radio drama. In a Life magazine review

of the broadcast, Sorry, Wrong Number was called “radio’s perfect

script.”43 Fletcher herself had said that she “wanted to write something

which by its very nature should, for maximum effectiveness, be heard

rather than seen,” a play that could only be performed on the air. In

fact, it was originally designed, she wrote, “as an experiment in sound

and not just as a murder story.” The telephone was to be the “chief

protagonist.” And then along came Agnes Moorehead. “In the hands of a fine

actress like Agnes Moorehead,” Fletcher said, “the script turned out to be

more the character study of a woman than a technical experiment, and the

plot itself, with its O. Henry twist at the end, fell into the thriller

category.”

[...]

Mrs. Stevenson

Goes to Hollywood

[...]

Like her

counterpart in radio, Barbara Stanwyck’s Leona Stevenson in the film is

confined to her bed and telephone. But this Mrs. Stevenson is not

invisible. She is, every bit, part of the extravagance that is her luxury

apartment. Leona first appears to the viewer in a medium shot, sitting up

in bed, clutching a large white phone receiver close to her head. It is

evening. The clock on her bedside table reads 9:24. Stanwyck’s Leona wears

a nightgown that repeats the pattern of embroidery on the upholstered

headboard and drapery, as if one with the interior design of the uptown

penthouse room. [...]

[...]

[...] On the phone

to the operator, Leona hears the click of the receiver on the other

extension, and realizes an intruder is in her apartment. She clasps her

hand over her mouth and hangs up, holding back further speech. She stifles

herself. The woman with the masterful voice no longer speaks. In her dying

struggle, Leona pulls the cover from the night table, sending the radio

tumbling to the floor. With the collapse of Leona, radio too takes a fall.

Two agents of auditory mastery are momentarily silenced—the drama’s

protagonist and the very technology that made her possible.

—Jeff

Porter, "Sorry, Wrong Number," Lost Sound: The Forgotten

Art of Radio Storytelling, U of North Carolina P, 2016.

|

Comprehension Check

- Who

is the "client" (149)?

- Sergeant

Duffy says that "Telephones are funny things" (157). What

does he mean by funny?

|

|

Study Questions

- What sounds play a role in

creating suspense in Sorry, Wrong Number and how?

- What is the role of light in the

play? Note lighting design such as spotlight behavior and

light-associated props like the lamp (148, 164) or

flashlight (165). What is the effect of spotlighting? How do

pacing and transition speed of stage lighting (sudden vs.

gradual) contribute to the narrative of the play? What

relationship is created between light and darkness? How does

light define darkness in the play? What is illuminated? What

is in darkness? What significance or meaning does the

light's description of play elements have?

- Consider irony in Sorry,

Wrong Number. You can focus first on an irony or a

scene with irony then connect it to or place it within the

context of the play as a whole. What is ironic? Why is it

ironic? How is the irony set up?

- How is connection conveyed?

- How is disconnection conveyed?

- What is the significance of the

food props? Consider the role of the sandwich (155), coffee

(156), and apple pie (157).

- Consider the function of time in

the play. Notice how time is marked, given or described, by

whom and for what reason. When is time precise and when is

it not? Why? How differently does time move throughout the

play? Does it move at an even pace? How is timing used? What

is the relationship between time and dialogue? In what ways

does time connect different people and things and in what

ways does time disconnect them?

|

Review Sheet

Characters

Mrs. Elbert Smythe Stevenson – "a querulous, self-centered neurotic"

(148); "I'm alone all day and night. I see nobody except my maid [...]

and the only other person is my husband Elbert—he's crazy about me—adores

me—waits on me hand and foot—he's scarcely left my side since I took sick

twelve years ago" (157)

1st Operator –

"Ringing Murray Hill 4-0098" (149)

Chief Operator,

Miss Curtis – "Middle-aged, efficient type, pleasant"

(152); "If it's a live call, we can trace it on the equipment. If it's

been disconnected, we can't" (152)

Sergeant Duffy –

"we'll take care of it, lady. Don't worry" (156); "Telephones are

funny things" (157); "Supposing you hadn't broken in on that telephone

call? Supposing you'd got your husband the way you always do? Would

this murder have made any difference to you then?" (157); "Unless, of

course, you have some reason for thinking this call is phoney—and that

someone may be planning to murder you?" (157)

1st Man – "You know the address. At

eleven o'clock the private patrolman goes around to the bar on Second

Avenue for a beer" (149); "Make it quick. As little blood as possible. Our

client does not wish to make her suffer long" (150); "A knife will be

okay. [...] remove the rings and bracelets, and the jewelry in the bureau

drawer. Our client wishes it to look like simple robbery" (150)

2nd Man, George – "A killer

type, also wearing a hat, but standing as in a phone booth" (149); "slow

heavy quality, faintly foreign accent" (149)

Places

Mrs. Stevenson's bedroom –

"Expensive, rather fussy furnishings" (148)

bed – "A large bed, on which Mrs. Stevenson, clad in bed-jacket, is

lying" (148)

phone booth – "In a phone booth" (149)

Time

night

–

11:00 p.m. – "At eleven o'clock the private patrolman goes around to

the bar on Second Avenue for a beer" (149)

11:15 p.m. – "At eleven-fifteen a subway train cross the bridge. It

makes a noise in case her window is open, and she should scream" (149)

Vocabulary

one-act

setting

props

lighting

sound effects

staging

script, playscript

plot

foreshadowing

suspense

conflict

motivation

coincidence

climax

resolution

character

characterization

dialogue

imagery

movement

pace

point

of view

diction

voice

tone

irony

- verbal irony

- dramatic irony

- situational irony

symbol,

symbolism, symbolic

theme

murder

terror

telephone

communication

connection,

connectedness; community; company; companionship

detachment;

isolation; aloneness

freedom

and confinement; possibilities and limitations

voice,

voicelessness

helplessness

frustration

arrogance

woman

in peril

illness;

disability; invalidism

life

and death

Sample

Student

Responses to Lucille Fletcher's Sorry, Wrong Number

Response

1::

|

|

Somchai Lee

2202234 Introduction to the Study of

English Literature

Acharn Puckpan Tipayamontri

September 15, 2018

Reading Response 2

Title

Text.

|

|

Reference

| Links |

Critical Articles

- Wendy Haslem, "Sorry, Wrong Number," Senses

of Cinema, vol. 37, 2005.

- David Crane, "Projections and Intersections:

Paranoid Textuality in Sorry, Wrong Number,"

Camera Obscura, vol. 17, no. 3, 2002, pp.

71–112. (Chula access)

- Amy Lawrence, "Sorry, Wrong Number: The

Organizing Ear," Film Quarterly, vol.

40, no. 2, 1986–87, pp. 20–27. (Chula access)

|

| Media |

|

- Sorry, Wrong Number, by Lucille

Fletcher, performed by Agnes Moorehead, Suspense, CBS

(1943 original West Coast broadcast; 29:56 min.)

|

|

- Sorry, Wrong Number, by Lucille

Fletcher, performed by Agnes Moorehead, Suspense, CBS

(1948 radio play, 28:35 min.)

|

|

- Sorry, Wrong Number, by Lucille

Fletcher, performed by Barbara Stanwyck and Burt

Lancaster, Lux Radio Theater, CBS (1950 radio,

55:51 min.)

|

|

- Sorry, Wrong Number, directed by

Anatole Litvak, performed by Barbara Stanwyck and Burt

Lancaster, Paramount (1948 film trailer; 2:38 min.)

|

|

- Kurt Anderson, "Sorry, Wrong Number," produced by

Devon Strolovitch, Studio 360, PRI (2015

retrospective on the radio play, includes interview with

Fletcher's daughter; 7:45 min.)

|

|

- On the Air: The Story of Radio

Broadcasting, Westinghouse (1944; 22:52 min.)

|

|

- Back of the Mike, Jam Handy

(1938 documentary about how radio drama during the gold

age was done; 9:15 min.)

|

|

- A History of the Telephone,

directed by Ronald Spencer, Pacesetter (1980; 19:10 min.)

|

|

- Operator,

directed by Nell Cox (1969 documentary; 17:00 min.)

|

|

- Switchboards, Old and New, Bell

Systems (1932 documentary; 13:21 min.)

|

Reference

Fletcher, Lucille. Sorry, Wrong Number.

24 Favorite One-Act Plays, edited by Bennett Cerf and Van H.

Cartmell, Broadway Books, 2000, pp. 147–65.

Further

Reading

Fletcher, Lucille. Sorry, Wrong Number

and The Hitch-hiker: Plays in One Act. Dramatists Play Service,

1952.

Home

| Literary Terms | English Help

Last updated September 25, 2018