Department

of English

Faculty of Arts,

Chulalongkorn University

The

Lottery

(1948)

Shirley Jackson

(December

14, 1916 – August 8, 1965)

"The Lottery" Notes

This short story was first published

in the June 26, 1948 issue of The New

Yorker.

138 civic:

- civic (Merriam-Webster)

: of or relating to a citizen, a city, citizenship, or community affairs

<civic duty> <civic

pride>

- Part

2 - Civic Activity Types, Oakland, California - Planning Code

17.10.130 - General description of civic activities.

Civic Activities include the performance of utility, educational,

recreational, cultural, medical, protective, governmental, and other

activities which are strongly vested with public or social importance.

138 paraphernalia:

- paraphernalia (Merriam-Webster)

3 a: articles of equipment:

furnishings b: accessory

items: appurtenances

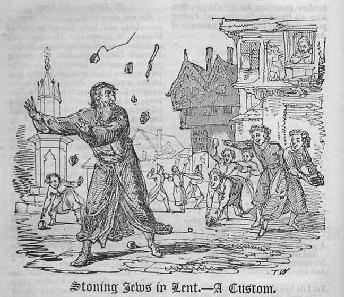

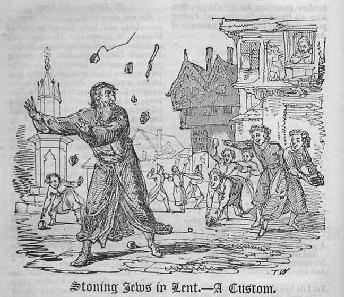

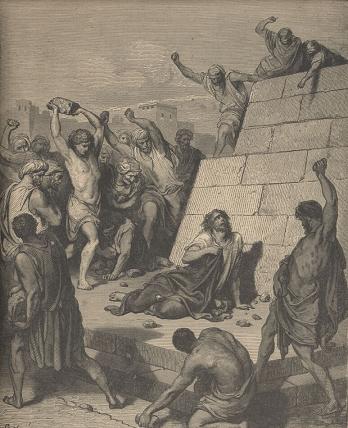

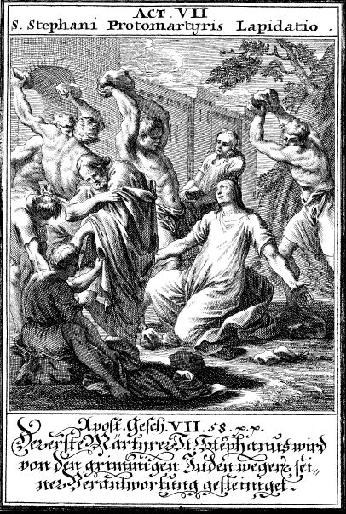

145 A stone hit her on the side of

the head: Stoning as a form of punishment and execution has a long

history. Like execution by firing squad, the group killing the subject will

simultaneously and continuously hit the subject until he or she is dead.

Stoning Jews in Lent.—A custom.

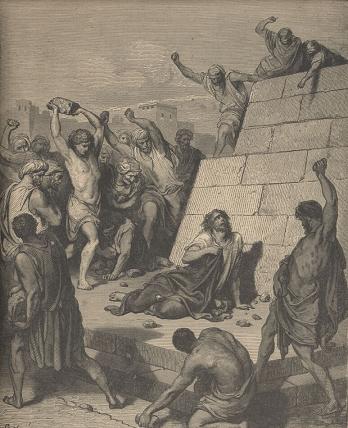

Doré, Gustav. The Martyrdom of

St. Stephen. The Dore

Bible Gallery. Chicago: Belford-Clarke, 1891.

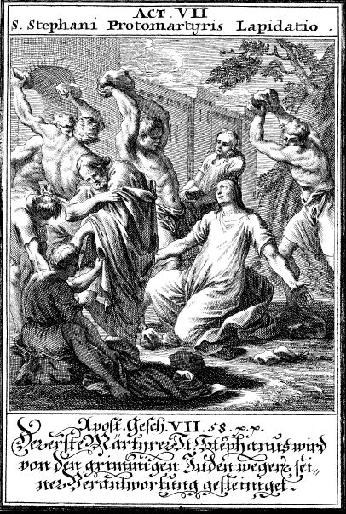

Weigel, Christoph. St. Stephani

Protomartyris Lapidatio. Biblia

Ectypa. Augsburg: n. p., 1695.

Erasmus, Desiderius. Noui

Testamenti æditio postrema. N.p.: apud Io. Frobenium,

1523.

|

- stone (transitive

verb) (Merriam-Webster)

1: to hurl stones at;

especially: to kill by pelting with stones

2 archaic:

to make hard or insensitive to feeling

3: to face, pave, or

fortify with stones

4: to remove the

stones or seeds of (a fruit)

5 a: to rub, scour, or

polish with a stone b:

to sharpen with a whetstone

Examples of STONE

He was stoned to

death for his crimes.

Stone the peaches

before serving.

- to cast the first stone (The

Phrase Finder)

- John

8:1–11:

1 Jesus went unto the mount of Olives.

2 And early in the morning he came again into the temple, and

all the people came unto him; and he sat down, and taught

them.

3 And the scribes and Pharisees brought unto him a woman taken

in adultery; and when they had set her in the midst,

4 They say unto him, Master, this woman was taken in adultery,

in the very act.

5 Now Moses in the law commanded us, that such should be

stoned: but what sayest thou?

6 This they said, tempting him, that they might have to accuse

him. But Jesus stooped down, and with his

finger wrote on the ground, as

though he heard them not.

7 So when they continued asking him, he lifted up himself, and

said unto them, He that is without sin among you, let him

first cast a stone at her.

8 And again he stooped down, and wrote on the ground.

9 And they which heard it,

being convicted by their

own conscience, went out one by one, beginning at the

eldest, even unto

the last: and Jesus was left alone, and the woman standing in

the midst.

10 When Jesus had lifted up himself, and saw none but the

woman, he said unto her, Woman, where are those thine

accusers? hath no man condemned thee?

11 She said, No man, Lord. And Jesus said unto her, Neither do

I condemn thee: go, and sin no more.

- John

10: 31–39:

31 Then the Jews took up stones again to stone him.

32 Jesus answered them, Many good works have I shewed you from

my Father; for which of those works do ye stone me?

33 The Jews answered him, saying, For a good work we stone

thee not; but for blasphemy; and because that thou, being a

man, makest thyself God.

34 Jesus answered them, Is it not written in your law, I said,

Ye are gods?

35 If he called them gods, unto whom the word of God came, and

the scripture cannot be broken;

36 Say ye of him, whom the Father hath sanctified, and sent

into the world, Thou blasphemest; because I said, I am the Son

of God?

37 If I do not the works of my Father, believe me not.

38 But if I do, though ye believe not me, believe the works:

that ye may know, and believe, that the Father is in me, and I

in him.

39 Therefore they sought again to take him

|

|

Comprehension Check

- What is the meaning of Delacroix

in French?

- What does "my old man" (140)

mean?

|

|

Study Questions

-

Compare

the first sentence of the story to the last. What

image does each describe? How clear is the scene

introduced in the beginning sentence of the story? In

what way is the clarity of the first sentence

different from that of the last? Can one say that the

last sentence is vivid even though it is not a direct

depiction like "the flowers were blossoming profusely"

(137)? Explain.

-

"The

villagers kept their distance" from the stool with the

black box on it, and were hesitant to step up when Mr.

Summers asked for help holding it (138). How does the

later description of the history and physical

condition of the black box including how it is treated

and kept during the rest of the year (139) affect that

initial impression of the lottery box?

-

What

associations does the word lottery

normally evoke? How does its being the title

of this story affect its meaning and that of the

unfolding events?

-

At

what point did you begin to suspect that the lottery

in the story is not our usual understanding of it?

What in the text tipped you off?

-

Do

you think aligning the lottery to "the square dances,

the teenage club, the Halloween program" is

appropriate (138)? Why or why not?

-

How

do you explain the smiles and laughter in the story?

The villagers are constantly joking with each other

and expressing good humor, yet what are we to make of

Mr. Summers and Mr. Adams "grinn[ing] at one another

humorlessly and nervously" (141)—presenting an

expression of good humor that is humorless? What is

the difference between Mrs. Hutchinson saying "'Get up

there, Bill...and the people near her laughed" (142)

and "Davy put[ting] his hand into the box and laughed"

(144)?

-

Laurence

Jackson Hyman, Jackson's son, mentioned in an interview

that "My mother took great care with the names of her

characters. When their names are common, that is

intentional, and when she names them Summers and

Graves and Constance and Oakes she does so with much

meaning." Notice how the names of characters in "The

Lottery" are used. Are they critical and evocative in

the same way the word lottery

is used? What meaning do they give to the

story?

-

Browse

through the list of common errors in reasoning on Purdue

Owl or on the Internet

Encyclopedia of Philosophy. What fallacies do

you find the villagers committing in "The Lottery"?

-

How

does Mr. Adam's mentioning the north village

considering not doing lotteries set up for his actions

at the end of the story?

-

What

significance do you find in Jackson's making a point

to describe several individuals' behavior in quite

attentive detail as each draws the lottery?

- Time

-

What

consequences of the passage of time are shown in the

story? How does time affect physical things like

objects and population compared to non-physical or

less tangible things like language, memory and

attitude?

-

After

finishing "The Lottery," how differently do you view

the various expressions that have to do with time

(ex. "Little late today, folks," "get this over

with," "You're in time," "Time sure goes fast," "Go

on," "Get up there," "Come on," "hurry up")

throughout the story?

-

The

description early in the story, "no one liked to

upset even as much tradition as was represented by

the black box" seems to indicate a strong resistance

to change among the villagers (139). Yet, "so much

of the ritual had been forgotten or discarded," this

latter even suggesting intentional

doing away with something. If the people are so

unwilling to instigate anything new, how is it that

so many changes or transformations have happened in

the village? Consider what remains static and what

becomes different (also how much and how long ago),

and how these affect or will affect the lottery.

-

Aside

from the movement of time itself, notice also the

movement in time

of the characters in the story. In some instances,

like for Jack Watson, he is urged to "'Take your

time, son'" as if to slow him down (143), in others,

like for Mrs. Dunbar, she is prompted with "'Go on,

Janey'" as if to hurry her up (142). Mrs. Dunbar

repeats "I wish they'd hurry." Mrs. Hutchinson says

"'You didn’t give him time enough to choose'" and

"'I think we ought to start over'" (144); she does

not say "I think we should stop." "There was a long

pause, a breathless pause" (143) and there were

hesitations (138, 144). Mr. Summers oddly comments

"'that was done pretty fast, and now we've got to be

hurrying a little more to get done in time'" (143).

Why these dances in time or with time?

- Like

the word lottery, several terms and phrases

alter in meaning once you have finished the story and

look back on them in hindsight. Consider the charged

implications of the following, for example:

- The

children assembled first, of course.

- "Bill,

she made it after all"

- "Wife

draws for husband" (141)

- "Horace's

not but sixteen yet," Mrs. Dunbar said regretfully.

(141)

Writing

Prompts

-

Discuss

forces at play in “The Lottery.”

Consider forces at play in the story. What factors

influence behavior, happenings, outcome, or changes

that occur? What conditions shape events? Which people

determine actions? Consider the ways these players

enhance or interrupt another. Also worth noting is the

trajectory of such social, personal, familial,

natural, or ideological forces in relation to the

plot.

-

Discuss

the central figure of the lottery.

What is “the lottery”? What does it entail? Track its

movement throughout the narrative. Consider also its

backstory. How and when does it begin? How does it

transform along the way? What continuities, shifts,

ironies, or inconsistencies do you see in its

depiction and role in the story?

-

Discuss

kinds of violence in the story.

What kinds of violence are in evidence in “The

Lottery”? What words suggest or describe violence?

Where is violence? How is it presented? What does it

do? In what way are the types of violence different?

How does each form of violence develop through the

story?

-

Discuss

fact and fallacy in “The Lottery.”

What are the facts in the story? What are the

fallacies? What are the fallacies about? You might

wish to examine, for example, the way truth and

mistaken belief are given in the narrative and the

extent to which each affect people’s knowledge and

actions.

- Discuss

names and meanings in “The Lottery.”

Consider the names and meanings of people, things, and

actions in this story. How do words’ denotations compare

to their meanings and connotations created within the

story? What connection or contrast might the characters’

names have to their personality, position, or behavior?

|

Review Sheet

Characters

Mr. Graves,

Harry

– the postmaster (138); "The night before the lottery, Mr. Summers

and Mr. Graves made up the slips of paper and put them in the box" (139);

"it [the black box] had spent one year in Mr. Grave's barn" (139); "There

was the proper swearing-in of Mr. Summers by the postmaster, as the official

of the lottery" (139)

Mr.

Summers, Joe

– "the official of the lottery" (139); "a round-faced, jovial

man...ran the coal business" (138); "The lottery was conducted—as were the

square dances, the teenage club, the Halloween program—by Mr. Summers, who

had time and energy to devote to civic activities" (138); "Every year,

after the lottery, Mr. Summers began talking again about a new box" (139);

"declared the lottery open" (139); "in his clean white shirt and blue

jeans" (140)

Old Man Warner –

"the oldest man in town" (138); "'Pack of crazy fools,' he said.

'Listening to the young folks, nothing's good enough for them.'"

(142); "'Seventy-seventh year I been in the lottery'" (142); "'It's not

the way it used to be,' Old Man Warner said clearly. 'People ain't the way

they used to be" (145)

Tess

Hutchinson, Tess, Mrs. Hutchinson – wife of Bill

(145); "came hurriedly along the path to the square...'Clean forgot what

day it was'" (140); "'It isn't fair, it isn't right,' Mrs. Hutchinson

screamed" (145)

Bill Hutchinson –

husband of Tess (145)

Bill Hutchinson, Jr., Billy – son of Tess and

Bill (144); "his face red and his feet overlarge, nearly knocked the box

over as he got a paper out" (144)

Nancy Hutchinson –

daughter of Tess and Bill (144); twelve years old (144);

Davy

Hutchinson – youngest son of Tess and Bill (145); "Davy put his

hand into the box and laughed" (144); "someone gave little Davy Hutchinson

a few pebbles" (145)

Mr.

Adams, Steve

– "'They do say,' Mr. Adams said to Old Man Warner, who stood next

to him, 'that over in the north village they're talking of giving up the

lottery'" (142); "Steve Adams was in the front of the crowd of villagers,

with Mrs. Graves beside him" (145)

Mrs. Adams –

"'Some places have already quit lotteries,' Mrs. Adams said" (142)

Mrs.

Delacroix – "'Seems like there's no time at all between

lotteries any more'" (141)

Clyde

Dunbar – "'He's broke his leg, hasn't he?'" (140)

Mrs.

Dunbar, Janey

– wife of Clyde (141)

Horace

Dunbar – son of Clyde and Janey Dunbar (141); sixteen years old

(141)

Mr. Martin

– "there was a hesitation before two men, Mr. Martin and his oldest

son, Baxter, came forward to hold the box steady on the stool while Mr.

Summers stirred up the papers inside it" (138)

Baxter Martin

– oldest son of Mr. Martin (138, 139)

Jack

Watson – "'I'm drawing for m'mother and me" (141)

Setting

Place

village

square – "The people of the

village began to gather in the square, between the post office and the bank,

around ten o'clock" (137)

Time

June – "The morning of June

27th was clear and sunny, with the fresh warmth of a full-summer day" (137)

Vocabulary

irony,

ironic

- verbal irony

- dramatic irony

- situational irony

contrast

setting

diction;

denotation, connotation

imagery

- visual imagery

- auditory imagery

- tactile imagery

- olfactory imagery

- gustatory imagery

- kinesthetic imagery

- thermal imagery

allegory, allegorical

symbol,

symbolic, symbolism

Character,

Characterization

major characters

minor characters

stock or type characters

stereotypes

double

confidant(e)

villain

hero

anti-hero

foil

self-revelation

personality

direct presentation of character

indirect presentation of character

show v. tell

consistency in character behavior

motivation

plausibility of character: is the character credible? convincing?

flat character

round character, multidimensional character

static character, unchanged

developing character, dynamic character, active character

direct methods of revealing character:

- characterization through the use of names

- characterization through physical appearance

- characterization through editorial comments by the author, interrupts

narrative to provide information

- characterization through dialog: what is said, who says it, under what

circumstances, who is listening, how the conversation flows, how the

speaker speaks (ex. tone, stress, dialect, diction/word choice)

- characterization through action

indirect characterization

Plot

Freytag's Pyramid

beginning, middle, end

scene

chance, coincidence

plot, main plot, minor plot,

subplot, underplot, double plot,

story

conflict, internal conflict, external conflict, clash of actions, clash of

ideas, clash of desires, clash of wills, major, minor, emotional, physical

- man v. self

- man v. man

- man v. society

- man v. nature

- man v. the supernatural

- man v. machine/technology

protagonist

antagonist (antagonistic)

suspense (suspenseful)

mystery (mysterious, mysteriously, mysteriousness)

dilemma

surprise (surprising, surprised)

plot twist

ending

- happy ending

- unhappy ending

- indeterminate ending (ambiguous)

- surprise ending (unexpected)

artistic unity (unified)

time sequence

exposition

in

medias res

complication (complicate)

rising action

falling action

crisis

climax

anti-climax (anti-climactic)

conclusion (conclude, conclusive)

resolution (resolve, resolving)

denouement

flashback, retrospect

back-story

foreshadowing

causality

plot structure

initiating incident

epiphany

reversal

catastrophe

deus

ex machina

disclosure, discovery

movement, shape of movement

trajectory

change

focus

Point

of View

third-person point of view

intrusive narrator

unintrusive/impersonal/objective narrator

limited point of view

omniscient point of view

editorial omniscience

neutral omniscience

selective omniscience

limited omniscient

second-person point of view

first-person point of view

self-conscious narrator

fallible, unreliable narrator

first person observer

first person participant

innocent eye

Sample Student

Responses to Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery"

Response 1: (from

text to writing)

Study Question: Discuss kinds of violence in the story.

What kinds of violence are in evidence in “The Lottery”? What words

suggest or describe violence? Where is violence? How is it presented?

What does it do? In what way are the types of violence different? How

does each form of violence develop through the story?

| Shirley Jackson's "The

Lottery" |

Close Reading |

Written Response |

|

“How

many kids, Bill?” Mr. Summers asked formally.

“Three,”

Bill Hutchinson said. “There’s Bill, Jr.,

and Nancy, and little Dave.

And Tessie and me.”

“All

right, then,” Mr. Summers said. “Harry, you got their tickets

back?”

Mr.

Graves nodded and held up the slips of paper. “Put them in the

box, then,” Mr. Summers directed.

“Take Bill’s and put it in.”

“I think

we ought to start over,” Mrs.

Hutchinson said, as quietly as she

could. “I tell you it wasn’t fair.

You didn’t give him time

enough to choose. Everybody

saw that.”

Mr.

Graves had selected the five slips and put them in the box, and he

dropped all the papers but

those onto the ground, where the breeze

caught them and lifted them off.

“Listen,

everybody,” Mrs. Hutchinson was saying to the people around her.

“Ready, Bill?” Mr. Summers asked, and Bill

Hutchinson, with one quick glance

around at his wife and children, nodded.

“Remember,”

Mr. Summers said, “take the slips and keep them folded until each

person has taken one. Harry, you help little Dave.” Mr. Graves

took the hand of the little boy, who came willingly

with him up to the box. “Take a paper out of the box, Davy,” Mr.

Summers said. Davy put his hand into the box and laughed.

“Take just one paper,” Mr. Summers said. “Harry, you hold

it for him.” Mr. Graves took the child’s hand and removed the

folded paper from the tight fist and held it while little Dave

stood next to him and looked up at

him wonderingly.

|

→ formally; as if he

doesn’t already know

→ Jr. is younger Bill; Nancy must be younger; “little” is

explicitly attached to the baby Dave

→ directed;

as if need directing?; the word directing give false direction?

→ start

over; not stop?

→ quietly;

as if holding down hysteria

→ wrong

time/too late to question fairness?

→ too

late/useless to ask for time

→

claiming/stressing everybody; seeing as witnessing; many kinds of

excuses/appeals used in protest

→ no longer

regarded when not in use

→

breeze/nature dissipates lottery (not people? differently from

people?)

→ appeals

to hearing now (v. seeing earlier); others speak over as if didn’t

hear (like “formally” and “directing”?): external action does not

reflect internal knowledge or feelings

→ last

glance as if saying goodbye?

→ remember;

as if need reminding

→ willing

boy v. others unwilling?

→ laughs v.

others somber

→ Dave

looking v. others seeing; what's the difference between to look

and to see?

→

wonderingly; childish wonder shows innocence, incomprehension of

meaning/implications of what’s happening

|

Soft Violence

For a

story famous for its lingering violent impact, Shirley Jackson’s

“The Lottery” offers very little actual violence. As a matter of

fact, “A stone hit her on the side of the head” is the only

explicit act of physical violence that occurs (50). And this sole

hard evidence describes a violence without a face attached to it

even though the entire village of three hundred something people

apparently know each other well, and not only because they have

done this yearly for generations.

The final

phrase, “and then they were upon her,” is swift, direct and vivid,

yet ironically vague. Arguably the only other description of

obvious violence in the entire story, it leaves the actual actions

to one’s imagination and understanding. The sense of violence,

however, pervades the story and is not only felt in these two

places. It is conveyed in very unlikely phrases and descriptions.

That flimsy pieces of paper can deliver a killing blow, that

little Davy’s few pebbles can feel almost more violent than Mrs.

Delacroix’s “stone so large she had to pick it up with both

hands,” that a mere sigh from the crowd can be damning, that

something as quiet and positive as a whispered hope for a friend’s

safety (“I hope it’s not Nancy”) can reverberate to “the edges of

the crowd” and imply a twelve-year-old girl wishing death on

anyone else in that friend’s family, that so little, so soft, so

insubstantial a thing as innocence can be marshaled to create

ferocity are testaments to Jackson’s word craft. In the

assumption-bending “Lottery,” violence is soft, residing in such

places as the laugh of a baby boy because it is a laugh of an

unknowing young son, effectively making himself an orphan, as he

enjoys becoming the killer of his own mother.

|

Response 2:

Study Question: The act of reading rests upon some

familiar ground or structure like grammar and language conventions with

the understanding that some new information is proposed. Likewise, a

story works because on some foundation of recognizable elements, it

offers something unknown. Discuss an example of such interplay between

expectations and surprise in one of the stories we have read.

|

Yada Manachujit

2202234 Introduction to the Study of English

Literature

Acharn Puckpan Tipayamontri

July 2, 2007

Reading Response 2

The Unchangeable

Changeable Lottery

There

is an unchangeability to sayings like those that Old

Man Warner recites in response to Mr. Adams’

bringing up possible giving up of the lottery.

Things like language or tradition also look very

stable or static if we view them for a short period.

At the moment of stoning, the ritual would seem to

Tess Hutchinson unshakable and eternal. Her pleas,

“Listen, everybody” (144), “It isn’t fair, it isn’t

right” (145) seem to fall on deaf ears, unable to

bend any rules or budge attitudes even slightly.

They seem as rigid as the stones being cast at her.

The surprise is that this is an optimistic story. As

a catalog of families predictably roll called in

alphabetical order are given and as questions to

which everyone “in the village knew the answer

perfectly well” are asked formally, catalogs of

change are also rattled off: family names will

transform and transfigure—Delacroix becomes

Dellacroy (138), black boxes will grow shabbier and

disintegrate (139), rituals will be “forgotten or

discarded.” The descriptive narrative moving

carefully from one set procedure to the next can

feel plodding. However, the procedures are anything

but set. “A recital of some sort,” for example,

“years and years ago, this part of the ritual had

been allowed to lapse” (139–40). Likewise the

“ritual salute” (140).

On

this perfect summer day, despite the horrific

community murder of one of their own, the revolting

violence of friends killing a friend, of a husband

killing his wife, and sons, daughters, and a baby

killing their own mother, this is not a tragic

story. It is a story about change that you do not

even have to hope or work for because it will come

any way. There is indeed revolt underway. One such

unavoidable upheaval: with the population’s growth,

“it was necessary to use something that would fit

more easily into the black box” instead of the

original chips of wood (139). Another more subtly

worded but no less a change: “it was felt necessary

only for the official to speak to each person

approaching” (140). Both ironic necessities. If the

lottery is necessary, it should be “unable to be

changed or avoided” (Merriam-Webster). Here we have

an almost oxymoronic expression “felt necessary”

where necessity is not a must but a feeling. The

story’s abrupt close on a projected action creates a

momentum that actually carries it beyond its

physical boundaries. The long view of that path that

Jackson casts with the careful rolling of her dark

story is that happily, the lottery will come to an

end.

|

|

| Links |

- Shirley

Jackson, "Biography

of a Story," Come

Along with Me (1968)

- "What

'The Lottery' Taught Shirley Jackson about Her Readers,"

Reader's Almanac, Library of America (2010)

- Ruth

Franklin, "'The

Lottery' Letters," Page-Turner, The

New Yorker (2013)

- William

Brennan, "How

Shirley Jackson Wrote 'The Lottery,'" Slate

(2013)

- Cynthia

Haven, "Shirley

Jackson’s “The Lottery” – it wasn’t as easy as she

claimed," Stanford University (2013)

- Cressida

Leyshon, "Shirley

Jackson," The New

Yorker (2014; interview with Jackson's son

Laurence Jackson Hyman)

- A. M. Homes,

"Introduction:

The Lottery by Shirley Jackson"

- Rich Kelley,

"The

Library of America Interviews Joyce Carol Oates about

Shirley Jackson," Library of America (2010)

- Jonathan

Lethem, "Monstrous

Acts and Little Murders," Salon

(1997)

- Angela Hague,

"A

Faithful Anatomy of Our Times," Frontiers:

A Journal of Women Studies (2005; Chula access)

- Robert

Armitage, "Some

Thoughts on Shirley Jackson," New York Public

Library (2009)

|

Media

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- "The Lottery," Journey Into..., NBC

(1951 radio adaptation; audio clip; story proper begins at

11:00 min.)

|

|

- The Lottery, dir.

Daniel Sackhiem, perf. Dan Cortese and Kerri Russell (1996

film inspired by Jackson's short story)

|

Reference

Jackson,

Shirley. "The Lottery." The Magic of Shirley Jackson, edited by

Stanley Edgar Hyman, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1969, pp. 137–45.

Further

Reading

Jackson,

Shirley. 9 Magic Wishes.

Crowell-Collier P, 1963.

Jackson,

Shirley. "Island."

By and about Women: An Anthology of

Short Fiction, edited by Beth Kline Schneiderman, Harcourt

Brace Jovanovich, 1973.

Jackson,

Shirley. "The

Bus." The Best American Short

Stories 1966, edited by Martha Foley and David Burnett,

Houghton Mifflin, 1966.

Home | Introduction to the Study of English

Literature | Literary Terms

Last updated August 26, 2019